-

Basking in the fall sunlight

-

Even my 🐈 enjoys Super Turrican: Director’s Cut, a restored genuine Super Nintendo game that’s bundled with the Analogue Super NT retro console.

-

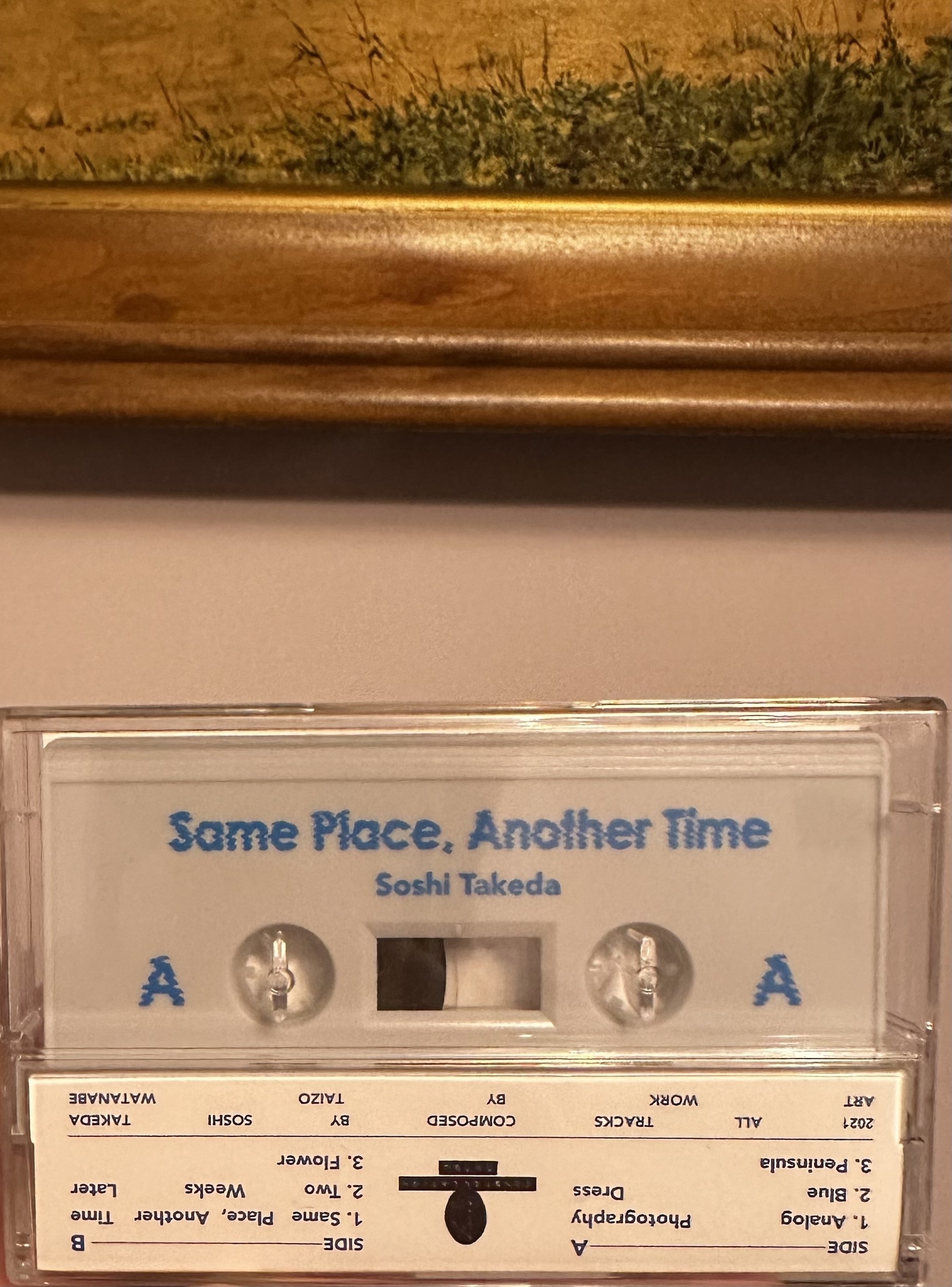

Some cassette tape listening

-

Diet culture, exposed: the legacy of Requiem for a Dream

“I’m thinking thin!”

In the 2000 film Requiem for a Dream, that’s the hopeful refrain from Sara Goldfarb (played extravagantly by Ellen Burstyn) as she embarks on a crash diet—black coffee, hard-boiled eggs, and half a grapefruit each morning—to lose 10 lbs in 10 days. The underlying goal (because there’s always one with dieting, no one diets for its own sake): Fit into an old red dress she wants to wear when she appears on television after winning a mail-in sweepstakes1.

Spoiler alert for a 23-year old movie: She can’t stick to the diet and so she seeks medication to assist her weight loss. A doctor prescribes her a daily course of amphetamines, i.e., the diet pills du jour from when the story was set in the mid 20th century.

The results are stunning: She loses her 10 lbs and then some, but—shocker—that proves tough to sustain without increasing her dosage. Soon she’s psychotic, imagining the refrigerators talking to her and that the huckstery, infomercial-immersed host of the show she delusionally thinks she’ll be on is in her living room alongside her fantasized thin red self2, mocking the messiness of her Brighton Beach apartment. Eventually she ends up virtually vegetative.

Her plot line, more so than the other three that involve three other characters’ struggles with heroin, is what makes Requiem for Dream linger3 in my mind. Rarely does any quasi-mainstream4 movie portray diet culture for what it really is—a money-making cult that drives its followers literally insane while destroying their health.

The notions that weight loss is A) desirable for health reasons and B) sustainable have no roots in scientific evidence.5 Any substantial weight loss is regained and then some in 95% of people. This inevitable weight cycling is itself far more provably harmful than being “obese”6—in other words, by telling people to diet, doctors are essentially prescribing the thing they’re nominally trying to prevent.

Medications for weight loss have a horrible track record. I mean, look at the fucking tables in this paper—and this was before the disastrous fen-phen cocktail of the 90s. As with the destructive baldness medication Propecia, weight-loss meds are pushed on the desperate public with zeal despite their concerning side-effect profiles7 and their relatively meager benefits8. I wouldn’t trust Wegovy et al. at all given the history and the culture that made them.

The weight loss imperative thrust on “obese” patients is an aesthetic and political concern—“fat people are disgusting,” more or less—masquerading as a medical diagnosis. And its costs are immense, not just financially but also in terms of the effects on people’s physical and mental health’s and their enjoyment of life. Perfectly good and nutritious food gets branded as “sinful,” “a guilty pleasure,” or part of a “cheat day/meal.” There’s thus a religious, Puritanical thrust to the dieting madness.

And for what? There’s no reward on the other side except for short-term weight loss that’ll be reversed, people who’ll tell you look great even if your weight loss was the result of some illness (the easiest way by far to lose weight, and a hint at how unhealthy it is), and more madness counting calories and going slowly mad in your home like Sara Goldfarb.

-

She never hears back about this contest. ↩︎

-

This reminded me in the imagery of the Laurent Garnier song “The Man with the Red Face.” ↩︎

-

The Cranberries? Anyone? ↩︎

-

It was rated NC-17 but it’s by Darren Aronofksy, a major director who also did the awful The Whale. ↩︎

-

On this point I recommend The Obesity Myth by Paul Campos. ↩︎

-

“Obese” is not a real disease. Its only indicator—BMI—is a pseudoscientific formula made upby a literal astrologer. I recommend What’s Wrong With Fat? by Abigail Saguy on how the “obesity epidemic” was manufactured from whole cloth in the 1990s. ↩︎

-

Propecia can cause irreversible damage to the male reproductive system. Wegovy can damage the thyroid, among other effects. Both come with an FDA “black box” warning. ↩︎

-

Yes, even the “miracle” new diet injections plateau and reverse after a while. ↩︎

-

-

There’s so many reasons to hate “obesity” discourse, including how it makes eating less fun by assigning a quasi-religious moralism—and from people who’d never consider themselves religious fanatics—to it. Yes, tell me more about how something is “sinful,” “empty,” “guilty,” or “cheating.”

-

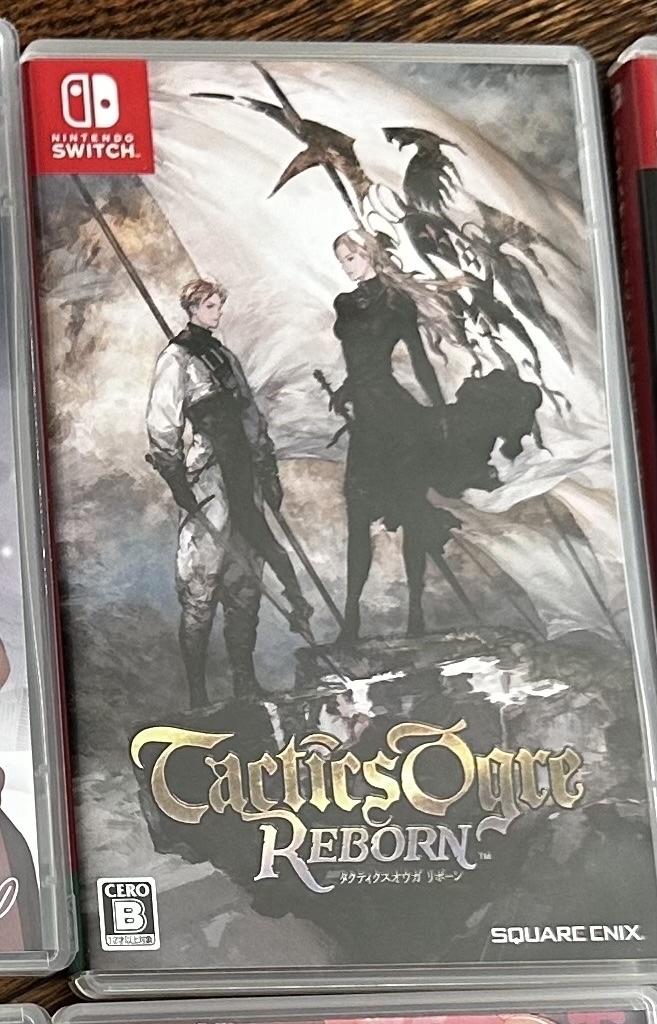

Collection of Super Famicom games

-

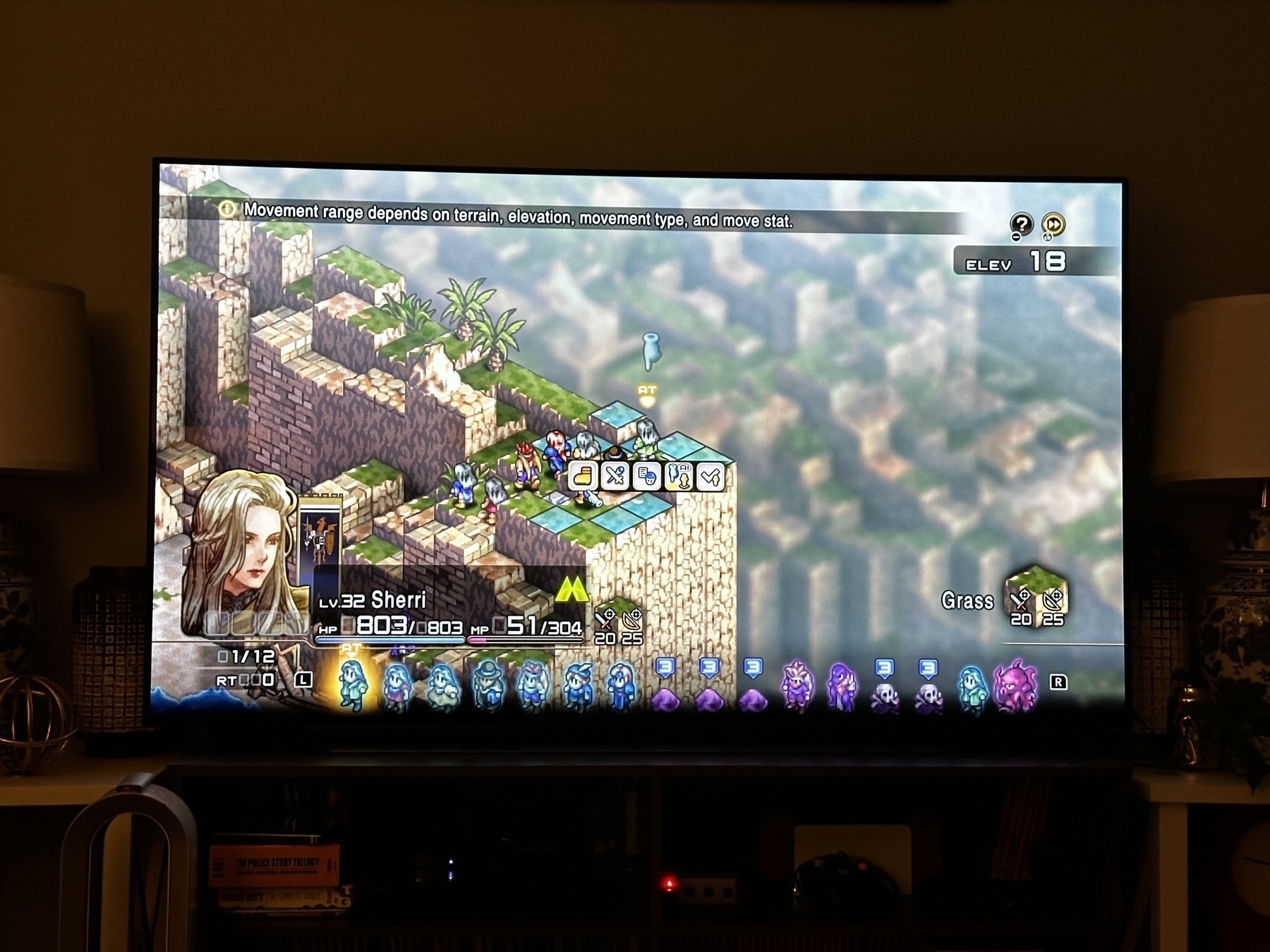

Amazing that Tactics Ogre came out in 1995 for the Super Famicom. The depth of its gameplay is way beyond anything else on the system or on many more “advanced” systems, too. The Reborn remaster spruces it up, but it’s still mostly the same basic 28 year old game underneath, and that’s incredible.

-

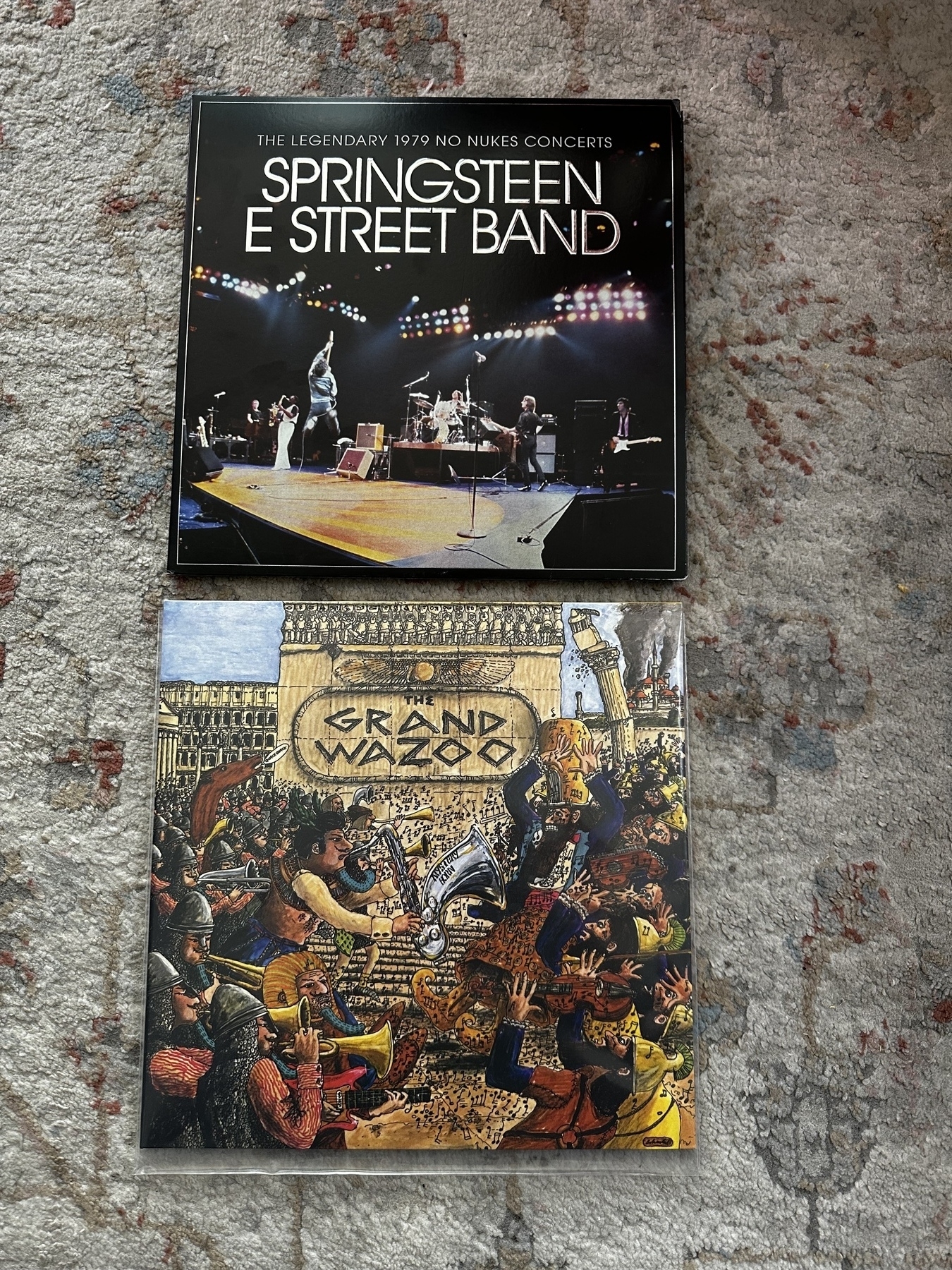

This morning’s listening:

-

Unless you exert conscious effort, you’ll deem the music of your youth as the “greatest” ever. Relatedly, music that others see as “great,” but that you aren’t nostalgic for, can seem mystifying—that’s happening to me with the current anniversary tours for The Postal Service and Death Cab for Cutie.

-

There’s a lot of media hype about Wegovy that doesn’t grapple with how at its core the drug seems to induce the same harmful weight cycling as every other miracle weight-loss “cure.”

-

Three versions of Pink by Boris:

- 2006 🇺🇸 CD

- 2006 🇺🇸 LP (different sequence, longer versions of 3 songs)

- 2016 deluxe 🇺🇸 CD (extra disc of bonus songs, 🇯🇵 cover art)

-

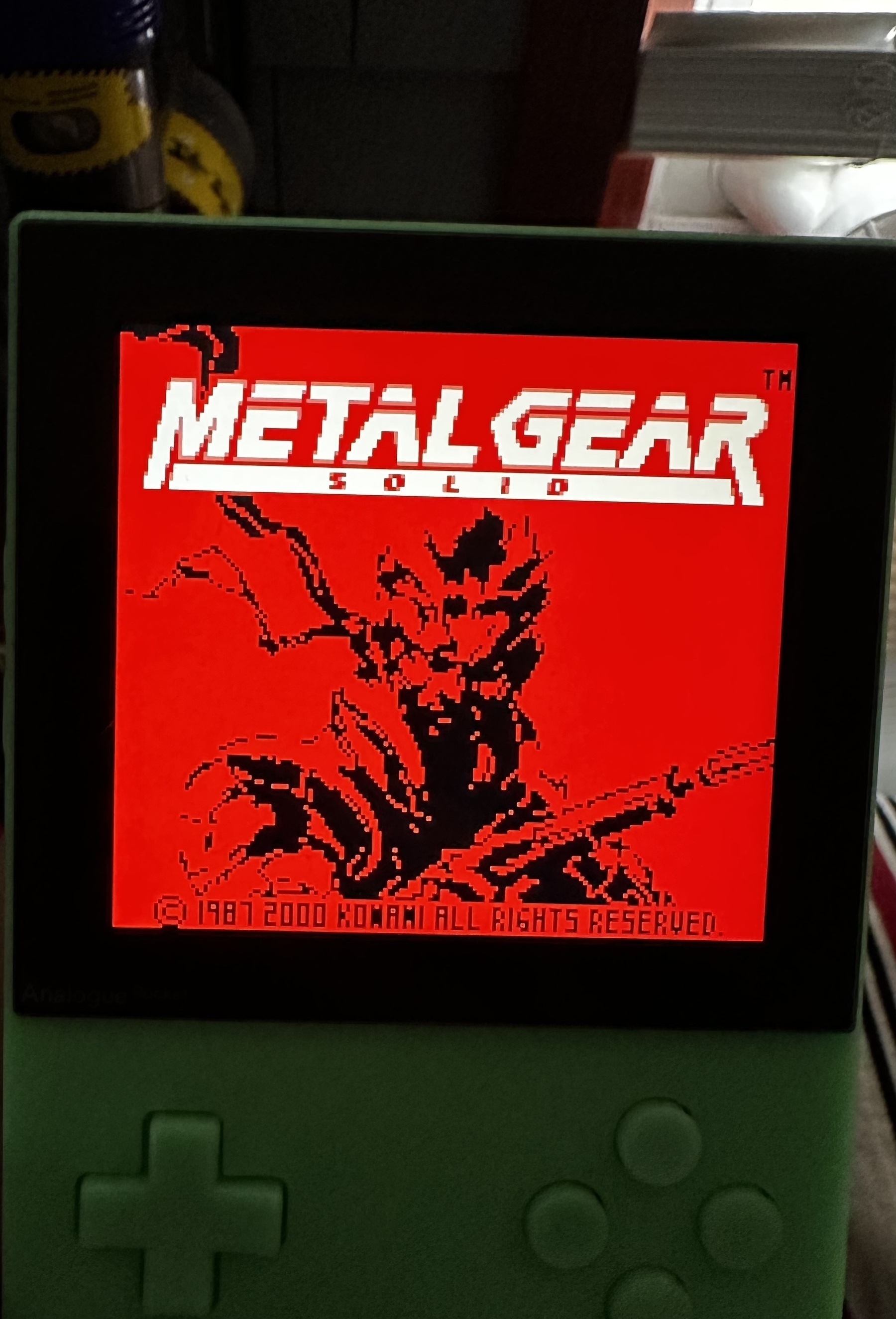

The Analogue Pocket has 100x (not a typo) the resolution of a Nintendo Game Boy Color (GBC). Here’s the title screen for the rare GBC title Metal Gear Solid, running off the original cart on the system.

-

The agony and the Ear-X-Tacy

Sometime in the mid 1990s, I saw it for the first time—the bumper sticker reading “Ear X-Tacy,” on a car in my school parking lot. That “X” had the mystique of the forbidden, at a time when deep, reflective narratives about Gen-X were widespread, and possibly when Elon Musk was already running the original X.com1. “X” still signified coolness and mystery.

The reality behind this “X” was straightforward but thrilling—Ear-X-Tacy was a vast, single-location record store in Louisville, KY, predominantly stocked with CDs2 that by the time I visited it with my mom a few years later had also gone big into a little new hotness called DVDs. It even carried vinyl, at a time when that format was at its nadir, right before its mid-2000s revival.

Shopping in the physical world

Shopping for music in physical stores like that one is an alien experience for most people under 30. It required immense time and literal energy—i.e., the gas to drive miles away—to go to Ear-X-Tacy, and as such couldn’t come close to the current efficiency of just searching a title in Apple Music and clicking the “+” button.

There’s no space for its mass comeback, and I doubt I’d trade the status quo for it. It’s easy to romanticize it now (and I will in a bit), but the requisite effort is what Don DeLillo might call a “collapsible fact”—something painful (in this case, the inconvenience and expense of CD shopping) that nevertheless gets tucked away as a form of self-defense, only to be recalled (uncollapsed, as it were) later when your nostalgia and/or idealism eventually wears off.

But hunting for CDs did feel challenging and visceral, because you had so much music (more than you could ever get through if you listened nonstop for a month3) at your fingertips as real physical objects, and yet simultaneously you had to work within the sharp physical constraints of the store itself. The experience was unique, such that, even now as a little treat to my nostalgia, I like to go to the Tower Records in Shibuya almost every winter to hunt through its massive rows of special edition Japan CDs4. It’s almost like going back to the mid 2000s again, the twilight of my frequent record-buying experience.

Though it was “only” ~15 years ago, those times seem even more distant than events from much earlier, I suppose because they were so thoroughly physical in away that no longer remotely resembles modern music consumption:

- I’d look up record reviews on Web 1.0 sites such as warr.org. Imagine—reading the opinions of professional critics!

- I’d write down the ones I wanted I to look for on a piece of printer paper. Paper! With pencils and maybe even pens!

- I’d either go with my mom on the drive to Ear-X-Tacy or, if I was in college, walk a ways to the Newbury Comics at a mall near campus. I had to leave the house!

- I’d finger through the CD rows, sometimes but often not finding what I’d been looking for, but also finding things I hadn’t thought of but seemed appealing. Not everything was available on-demand!

- I’d take the discs back to my room (or dorm) and use my desktop PC to rip them into iTunes and then load them onto my iPod. There was no “cloud”!

It took effort, and as painful as it often was, finding something rewarding and having it in your hands was exhilarating—a tangible win in a well-defined game with clear boundaries.

The Zappa conundrum

The artist who dominated those peak CD buying years was one who had at best a contentious and at worst a hostile relationship to the format—Frank Zappa. Record stores almost always organized their collections alphabetically by artist’s surname, so I built muscle memory5 to go to the end of the line and find the day’s almost always massive sample of Zappa’s endless discography.

They’d often have his most popular work—We’re Only In It For The Money, Apostrophe, Freak Out!—alongside some daunting (and expensive) multi-disc works such as Läther and Shut Up N’ Play Your Guitar, and lots of releases you’d probably never even heard of despite your preliminary research, such as Wazoo, a live album containing some but not all material from the much better-known The Grand Wazoo studio album.

Finding a worthwhile6 Zappa release took even more work, but had an even greater reward, than any artist I can recall, not just because there’s a huge gap between his best and worst work, or because he released seemingly 459 albums, but also because in the pre-digital panopticon, pre-smartphone era, it wasn’t always easy to know you’d got the right version of any given album.

Here’s where Zappa’s aforementioned contentious relationship toward the CD comes back in play. When CDs became commercially available in the 1980s. Zappa—like all other major artists of the album era—began remastering many of his LPs. But he went further: He actually re-edited and heavily remixed the recordings, making many of them sound drastically different from the vinyl originals:

- We’re Only In It For The Money had all of its original drum and bass tracks replaced with new recordings that sound badly out of step with the other instrumentation. It also has its censored obscenities restored. The initial CD was different from both the stereo and mono vinyl releases, which were also substantially different from one another.

- Hot Rats had one of this tracks, “The Gumbo Variations,” lengthened by 4 minutes, and its most famous piece, “Willie the Pimp,” re-edited with what sounds like a totally different guitar solo.

- Unless you’d snatched up and held into the original 8-track cartridge of Lumpy Gravy in 1967 when it got recalled, every version thereafter until 2009 was the vastly inferior 1968 re-edit with lots of irritating dialogue added. There was also another version that “punched up” that 1968 mix with re-recorded bass and drums!

There’s way more along those lines. Indeed, the endless possibilities opened up by the CD format—longer run times and greater dynamic range 6, mainly—seemed to overwhelm Zappa, giving him pretext to indulge his tendency to fiddle. Sometimes, limits are good!

I was lucky to walk out of Ear-X-Tacy in spring 2005 with a good mix (the 1995 CD) of We’re Only In It For The Money, I slipped it into a CD player while riding through a hilly stretch between Nelson and Washington Counties in Kentucky, and added it to my iPod later that day. But I also got a “bad” (to some people) mix (the 1987 CD) of Hot Rats and wouldn’t hear the “good” vinyl mix for years (FWIW, I think the CD sounds better).

Physical memories

Those two discs were the soundtrack to my 2005 summer—the drums of “Mom and Dad” echoing in my head while I assembled cars door panels in a factory, the squawking saxophone of “The Gumbo Variations” playing from the car stereo on our road-trips to Rhode Island. I was so careful with them because even then they seemed to embody, in their physical form, a time and place I could literally touch.

Sadly, I lost my Hot Rats disc in a flood this year and only barely saved the We’re Only In It For The Money one and have had to clean it; I think it may still be usable. Either one’s tracks—and all their alternate Zappa remixes, too—are of course still available on every streaming service, but not those exact tracks, on those exact discs, as physical links to distinct memories, and as manifestations of what versions of those albums were deemed the “right” ones at that historical juncture. That’s something that feels like a unique product of the “music store” era, and one that’s literally being washed away.

-

The old X dot com was an online bank that merged with Confinity to make PayPal. ↩︎

-

They even had a Super Audio CD (SACD) section. SACD was a format that required special playback equipment and offered only modest improvements over regular CDs, most importantly the ability to carry up to 6 channels of audio instead of just stereo. But basically nothing except the PlayStation 3 and some Blu-ray players offered a practical way to play them over a good sound system. ↩︎

-

I told a doctor that I had a month plus of music on my iPod in 2008 and I’m pretty sure that even now I haven’t listened to some of the songs in that batch. ↩︎

-

In Japan, CDs often have extra tracks or even extra discs exclusive to the country. ↩︎

-

I typo’d this as “music memory,” and almost left it. ↩︎

-

It’s not an exaggeration to say that with some of Zappa’s worst work, like the 1968 mix of Lumpy Gravy most people couldn’t endure even a single playthrough. ↩︎

-

Don DeLillo, on the last day of summer in Underworld: “It is all part of the same thing, the feeling of some collapsible fact that’s folded up and put away and the school gloom that traces back for decades—the last laden day of summer vacation when the range of play tapers to a screwturn.”

-

Like a 🐅 camouflaged in the jungle

-

Some ☕️ and 🌈

-

Bright red tomatoes from my backyard garden

-

“The economy” isn’t real—but your perceptions are

One of the inescapable meta-narratives of the Biden era had been centrist and center-left writers 1 wondering impatiently why so many Americans think “the economy” 2 is so bad when, in fact, it’s objectively so good. Will Stancil exemplified this tendency recently when he characteristically blamed “media vibes” for distorting Biden’s “economic approval”:

I really think the best explanation [of] Biden’s low economic approval is media vibes. People do not accurately perceive real-world economic indicators around them and predictably adjust their politics. Instead they internalize narrative descriptions of the world, mostly from media.

He has this exactly backward.

In Stancil’s formulation, the supposed real thing is the “real-world economic indicators” that can’t be “accurately” perceived, whereas “narrative descriptions” are fluff—harmful and fanciful distractions (“vibes,” a word meant to silly-ify and diminish their seriousness) from that hard underlying realness of unemployment rates, wage numbers, job openings, and so on. Moreover, “economic approval” gets set aside, presumably from others types of approval (social approval? political approval?), placed above (or maybe below, depending on the spatial metaphors) them as something more fundamental, more real.

But you can’t hold GDP per capita in your hand—after all, it’s a total abstraction, a statistical average! Meanwhile, all of the following things are super-tangible and accordingly easily captured by narratives that in turn resonate with huge audiences:

- The balance in your bank account strained in particular by healthcare costs and other emergencies that are pure products of the U.S. political system. 3

- The very prominent signage (practically a form of advertising) for gas prices, which are virtually unique among consumer goods in being touted in this way. The absolute level doesn’t even matter as much as the sensation of it moving in the “wrong” 4 direction.

- Political sentiments that make you feel like you’re“losing” or “winning” depending on who’s in office, regardless of what’s happening in “the economy.”

It’s the narratives that are the real and powerful things, and the macroeconomic indicators that are fake and impotent in people’s lives. And yet all of the concerns above and any adjacent to them—essentially, anything that strays from the perceived cold hard realness of “the economy” and of the discipline that studies it, economics—are treated as, well, fake news by the Stancils of the world. To them, there’s an objective economic reality out there and people are simply failing to get it because they can’t get out of their own ways.

This viewpoint is reminiscent of two others common on the American left, and you can see contours of both in the incredulity thrown at skeptics of the current U.S. “economy”:

- First, the constant characterization of right-wing climate deniers as idiots ignoring what’s before them.

- Second, the mockery of the belief that Hell awaits anyone who doesn’t grasp what religious fundamentalists deem the “obvious” truth of the Gospels.

Are economy deniers like the clueless climate deniers in no. 1, or are they more like the clueless evangelicals and tradcaths in no. 2? In this case, I think that’s the wrong question—the right one is “why do ‘the fundamentals of our economy are strong!’ proponents sound so much like those zealots in no. 2?”

What even is “the economy”?

Harsh? Sure. But the entire “why don’t they get how awesome ‘the economy’ is?” narrative hinges on a concept as flimsy as that of a mythical deity—that of “the economy” itself.

This term, meant to denote all of the activity in an entire country, only came into vogue after the Great Depression, and its indicators—the ones in which Stancil et al. invest so much value—are quite imprecise. Even the economist Diane Coyle, who wrote a book about GDP, says that the number is more of an idea than a thing. It doesn’t denote any “natural entity,” she says. It’s also somewhat nonsensical—for example, the Sisyphean rebuilding of infrastructure after every hurricane actually boosts Florida’s GDP. It’s good for “the economy,” even!

So “the economy” is a little wonky as a concept, but it’s still fundamentally sound as a meaningful term, about which people should be getting generally similar signals? No. The problem is that by cordoning off something called “the economy,” we act as if:

- There’s something amoral, scientific, and generally objective about it.

- It’s nicely separated from the messier fields of politics, social science, philosophy, art, and so on.

- Being free of such complications, it can be clearly—and uniformly—measured, perceived, and felt.

That’s all really naive. There’s no there there with “the economy”—it isn’t something that’s easily described even by its proponents, such as Coyle above, much less readily (or uniformly!) perceived by the population at-large. People’s own experiences in spheres beyond economics—where they were born, the music they listen to, their cultural heritages, their social circles—inevitably shape what they think about economics. It’d be weird if they didn’t!

Sometimes pundits do latch onto this, although they usually stop short of realizing that fixation on “the economy” is a category mistake. Judd Legum wrote a much more nuanced take than Stancil’s on the “what’s with people thinking the good economy sucks?” phenomenon and identified partisanship as a major reason for differing perceptions:

One factor in Americans' pessimistic view of the economy is partisanship. A study published in The Review of Economics and Statistics in May 2023 concluded that “partisan bias exerts a significant influence on survey measures” of economic conditions, and this influence is “this bias is increasing substantially over time.” Specifically, “individuals who affiliate with the party that controls the White House have systematically more optimistic economic expectations than those who affiliate with the party not in control.”

Think about how bad the Trump years felt if you were on the left, despite the “good” (for the stock market, at least) “economy” (whatever that is). Guess what, that feeling was real and you weren’t simply in denial about some deeper underlying economic truth that you should’ve accepted in such a way that you could compartmentalize everything else—the world is experienced through your total overlapping value system, not just (if even at fucking all) your relationship to economic statistics.

So wondering why everyone isn’t in lockstep, joyously buying into a shared notion of a “great economy” is akin to wondering why everyone hasn’t simultaneously accepted Jesus Christ as their personal lord and savior—given social cleavages and political differences of all kinds, some of them irreconcilable, that was just never going to happen, and you sound like a disappointed and spiteful preacher thinking that it ever would.

Samuel Chambers, in his collection There’s no such thing as “the economy”: Essays on capitalist value, sums up why any meta-narrative about “the economy” that treats it as a standalone domain is mistaken (emphasis mine):

An “economic” event is never just economic, and it never happens only in or to “the economy.” …[T]he so-called “economy,” understood as a discrete object or domain, only comes into existence as a construction of the discipline of economics, after which the very idea of such a place is reified by other disciplines (who explicitly or tacitly accept the idea that “the economy” is what economics studies). Every social order is woven together by threads that are simultaneously economic, political, cultural, and so on. Just as the economic, the political, and the social do not exist in, nor can they be confined to, separate spheres, so too for “values.” There is no moral domain, separable from others. Value systems are themselves built into, developed through, and secreted out of larger social orders. If we want to understand value relations, we cannot look to a discrete object or a separate value sphere; we can only ever look at society. This lines or argument entails the very impossibility of placing “the economy” on an ethical foundation, for the straightforward reason that one of the things “the economy” does is produce and restructure value relations.

So there—stop worrying about why everyone isn’t seeing the light of the wonderful Biden economy, and think about the political and social (and philosophical and moral and so on) reasons for why that might be.

-

I identify as a leftist. ↩︎

-

I’ve put this term in quotes throughout because I think it’s flimsy, as I’ll delve into later. ↩︎

-

A majority of Americans live paycheck-to-paycheck. ↩︎

-

“Are high gas prices good?” is a conundrum for the U.S. left because while high prices discourage driving an ICE vehicle, they also create powerful backlash narratives. ↩︎

-

Essential reading

-

Saw this red bird earlier on top of my 🍅 cages