-

The past isn’t quaint while you’re in it

Many once-ubiquitous customs and behaviors have become so obsolete that it’s puzzling to anyone who didn’t live through them—and maybe even some of us who did—how they were ever so dominant.

Sports gambling was very discreet

Turn on any major sporting event today and you’re likely to get bombarded with information directly from the announcers about betting spreads, “first bet free,” and upset implications. Moreover, many accompanying advertisements are also about gambling. FanDuel, DraftKings, et al. are tightly interwoven with the legitimate sports broadcasting complex. ESPN has licensed its name to a sportsbook maker. Gambling won.

Until the late 2010s, this all would’ve seemed gauche.

Watching a broadcast before then, you’d never know that anyone was betting on the event, much less get direct encouragement to do so yourself. In the 1990s, my grandpa sometimes mentioned moneylines to me, and asked me to look them up in the newspaper, but at that age I didn’t know what was going on, and I didn’t understand the scope of sports gambling until well into adulthood.

Indoor smoking was everywhere

When I was helping out at a bingo at a school around the same time as I was looking up those lines in The Courier-Journal, everyone smoked in the gym where the event was held. The smell went everywhere you went. Restaurants had (indoor) smoking sections.

Courseware? Never heard of it!

A Mastodon post sadly lost to time had a bit in it about how, in the Star Wars universe, the prevailing attitude toward cybersecurity seemed to be “never heard of it.” That was the same attitude colleges had about specialized education software such as courseware, before about 2005.

Indeed, I attended college in the 2000s and it was even then an intensely paper-driven process:

- Class papers were often turned in by dropping them in a faculty member’s department mailbox. Only near the end did email attachments become A Thing.

- All registrations were done by hand in ink on a paper card, until they were replaced after my junior year by a proprietary online system.

- Every course had a paper syllabus that had to be religiously referred to and preserved.

Now? The syllabus is another artifact of the Paper Age, as Ian Bogost explained in The Atlantic:

The syllabus encapsulated the educational side of college life. This wasn’t just a course plan; it was a document that mediated the student’s relationship with the professor. It was a contract, and those who paid that contract insufficient mind—students who might find themselves in breach—were considered lazy, incompetent, or truculent.

Then, 21st-century software upended how courses were run.

Courseware that tracks and updates every aspect of each class is now so embedded into college that you come off as a Certified Old if you say there was a time when it didn’t even exist.

Passwords and sign-ins were rare

Remembering passwords and, if you’re more bleeding-edge, managing 2FA logins and passkeys, is intensely important now. But you used to be able to use a computer all day without ever having to enter a credential to sign into anything.

Let’s say you’re using a Windows desktop 1 in 1996. Your workflow might be:

- Turn on the machine.

- Arrive at the Home Screen.

- Do some work in Microsoft Office and save it to a floppy.

- Print some documents

- Play a game off of a CD-ROM.

- Fiddle with Paint.

- Look at some pre-JavaScript webpages.

Signing into the cloud? Never heard of it.

Console gaming was a lot faster, actually

1995 was my banner year playing the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES). Although gaming has nominally advanced a lot since then, it’s impossible for most modern systems to match the sheer speed at which you could go from not playing to being immersed in a game. We’re talking just a few seconds, to turn on the CRT TV, power on the console, see a title screen, and press Start.

By contrast, modern systems may have to download a patch/update whose file size is bigger than the entire SNES library, before doing anything else. And then loading screens are everywhere. When Mickey Mania came out in 1994, its loading screens were considered painfully slow for the SNES, a console for which it wasn’t even fully optimized. Now those screens would be some of the speediest in console gaming.

Aging was a bigger deal

If you turned 40, people used to act like you were near death. 60? You may as well be mummified. Now there are septuagenarians who are fitter and more active than the 30somethings of the 1980s and 1990s. Modern medicine is astonishing. Lipitor didn’t come to the US until 1996!

Desktop PCs were ascendant

Everyone at my college had a tower desktop PC and a printer connected via serial port. I’d be surprised if anyone there now had a desktop or any kind in their rooms.

Video rentals were big business

The very small town I grew up in once had multiple video rental places. Walls of VHS tapes and SNES and Sega Genesis cartridges. Now physical entertainment media is the outpost of collectors and enthusiasts only.

Edgy white guys, not so much anymore

This one is harder to quantify but I feel like people used to speak in hushed tones about “edgy” white men geniuses such as Kurt Cobain and Lenny Bruce. That moment’s gone and it’s been gone for a while. When a cello duo came to my school in the late 90s, they were astonished that most of the audience had never heard of Nirvana.

-

I’ve always preferred Macs but I use a Windows example here because that’s what we had at the time and that era was the nadir of Apple’s business. It almost went bankrupt in 1997! ↩︎

-

The Old New Memories

Sometimes, events from many years ago can feel much closer to the present than much more recent ones. I was thinking about how just 6 years ago, Steve Bannon was a White House adviser and Mike Pence VP, and both of them apparently on good terms with then-President Trump. 1 Now you couldn’t gather the three in a room together without fisticuffs. The reality in which they were all somehow chummy feels like it may as well have happened during the Napoleonic Wars:

- Pictures from that era already have that dated look of several-times-superseded digital photography (the iPhone 7 was the latest generation at the time).

- Places I visited while fretting constantly about the carnage of the Trump-Pence WH have long since shut down, and so I feel like my one-time very tangible worries are now shapeless, homeless memories with no anchor in physical space.

- It wasn’t far from the COVID era (only 2 years and change!), so the immediacy to that rupture puts its datedness in even sharper relief.

And yet a The Mars Volta concert I went to more than 18 years ago—that feels like it just happened.

Like a lot of the music I discovered in the mid-2000s, I found out about them via Pitchfork, a music site now owned by Condé Nast but back then still indie and staffed by people as convinced of their own righteousness as any Twitter or Bluesky shitposter who thinks their addiction to what amounts to a digital casino gives them superior insights and even credentials as some kind of enlightened, hardened online laborers. Although I found and purchased plenty of albums on account of positive Pitchfork review, it was a nominally negative review of the first Mars Volta LP—penned by the same guy who wrote the worst album review ever—that drew me in:

The Mars Volta mistake sonic piling for complex architecture. No melodic themes are carried. Often you’ll find yourself lost in a epic passage of dripping noises (“Cicatrix ESP”) or a robotic bleepdown (“Take the Veil Cerpin Taxt”) where the song even forgets itself, before the opening riff and chorus blare back in an “oh, right, this one” kind of way. Even acoustic interludes, like the one during the opening of “This Apparatus Must Be Unearthed”, can’t pass without Amazon bird recordings and distant e-bow.

Amazon birds? Epic passages of dripping noise? Where do I sign up?

Both that album (De-Loused in the Comatorium) and its follow-up (Frances the Mute) were the soundtracks to my hazy March 2005, a month of major awakening and pain in which I began struggling with academic work but also saw a path toward a new identity and life as a 🏳️🌈 person. I’ll always remember blasting “The Widow” while working on art projects in my dorm.

Maybe it’s that association of the band’s music with a pivotal moment in life that makes even a concert from 2005 feel so immediate in my memory, more so than the much more recent Trump-Bannon-Pence triumvirate. That, and the fact that I have no photos or recordings of it, nothing to go on but my thoughts. So it’s a distinctly analog experience that has to be recreated anew from the raw materials of the mind forge each time.

The way the human brain works is that it doesn’t store perfect digital copies of anything that can be transported and recontextualized outside of the body that it’s apart of. One person’s memory is unique, even of events simultaneously experienced by numerous others. Accordingly, it’s possible that the aforementioned context made me uniquely predisposed to be blown away by that concert, at which they opened with a 20-minute song and ended with a 32-minute one, with their relatively concise “hits” (used loosely) “The Widow” and “L’Via L’Viaquez” sandwiched in between.

Was it really that great, objectively? Who can even say, given how each of our minds contextualizes and evaluates events differently? I’ll conclude with a passage from one of my favorite essays on this subject, “The Empty Brain”:

Whereas computers do store exact copies of data – copies that can persist unchanged for long periods of time, even if the power has been turned off – the brain maintains our intellect only as long as it remains alive. There is no on-off switch. Either the brain keeps functioning, or we disappear.

-

I’ve been watching Jonny Quest while working out and it’s very distracting how the show has a character named “Race Bannon” who is a dead ringer for a fitter Mike Pence. He also features in a few episodes of the Adult Swim show The Venture Bros. ↩︎

-

🐝 🌼

-

It was so tough to quit Twitter even in the Musk era, because it felt like a news source unique in both its depth and velocity. Now I realize that wasn’t true—I was just addicted to the dopamine 🎰. Plus, all that news was filtered thru the excruciating minutiae of intra-platform feuds and egos.

-

If I had to propose just one cause of 🇺🇸 ‘s current ills, it’d be cars—not only due to the environmental and health damage, but also because the land-use patterns they drive (everything’s far away, across a sea of traffic, noise, and danger) make it much harder to build and sustain friendships.

-

Now we’re all gamblers in the ESPN casino

ESPN—yes, the U.S. cable sports network—once offered a mobile phone plan.

In late 2005, the company launched Mobile ESPN, a sports-centric service delivered directly from the Bristol, Connecticut-based company to devices such as the Samsung ACE, via ESPN’s capacity as a mobile virtual network operator using extra capacity from Sprint 1. This expensive package—it could cost as much as $225 per month—also included voice and data alongside access to push notifications (e.g., about game scores) and live event coverage from ESPN, all of it a true novelty on handsets in the mid-2000s.2

Steve Jobs infamously called Mobile ESPN “the dumbest fucking idea I ever heard.” It shut down in late 2006, right before the original iPhone was unveiled in January 2007. Neat narrative, right?

Mobile ESPN was the future after all

But even though smartphones obviated the immediate utility of anything resembling the Mobile ESPN paradigm—wherein the “intelligence” is all server-side and the device is essentially just a dumb terminal, rather than the reverse, as seen with the iPhone in particular as well with the current trend toward on-device “AI” 3—the infrastructure built in 2005-2006 helped ESPN launch one of the most used and influential mobile apps. Moreover, Mobile ESPN looks in retrospect like a proto-streaming service—a hedge against the possible unfurling of the cable/satellite TV bundle, of which ESPN has long been the star and the most expensive single component.

Mobile ESPN revealed not only ESPN’s urge to be at the technical forefront (even with technology that wasn’t economically practical), but also the anxiety the company felt about the almost too-good-to-be-true economics of cable/satellite TV. It saw mobile phones as a potential threat to that business, and Mobile ESPN was its beachhead. To recap, cable/satellite TV is the perfect business model:

- If you’re a content maker like ESPN, providers such as Comcast and Charter pay you for the right to carry your channel.

- You can also run ads on your channel!

Streaming may seem so technologically modern in comparison, but it’s nowhere near as lucrative as pay TV—with these dual income streams—was at its peak. Disney+, Max, and Peacock all lose money or barely eke our a profit each quarter. ESPN even now as a cable/satellite-only channel 4 is still very profitable, but cord-cutting (i.e., the ditching of pay TV in favor of streaming services) has diminished both its reach and its bargaining clout. The New York Times recently documented how much ESPN would have to charge if it went “direct to consumer,” i.e., sold its main channel as a standalone streaming service rather than requiring people to purchase a pay TV bundle:

Estimates vary widely, but if ESPN offered its cable channels à la carte, it would most likely have to charge an astonishingly high fee for the streaming service, perhaps $40 or $50 per month, just to maintain its current revenue.

$50!!! Complaining about the high costs of pay-TV packages is practically an American tradition, but paying that much for one channel would be unheard of, not to mention insulting when even at this late date a basic cable bundle that includes ESPN and many other channels can still be had for less than $100.

Yet, according to Disney CEO Bob Iger, the standalone ESPN is a matter of when, not if. To me, the streaming ESPN feels like Mobile ESPN redux because it’ll be:

- Way too costly for the average consumer.

- Clunky and unreliable, if the Disney+ and Hulu interfaces are anything to go by.

- Likely to be superseded by some kind of bundle or streaming-native service, in the same way the iPhone was sort of a “bundle” or cheap apps in its early years, one that easily outstripped the dumb phones that Mobile ESPN was built for.

- Still fundamentally valuable, in that it’s delivering in-demand “content,” in this case, live sports.

Enter the gambler

At the same time that it’s trying to become a streaming service, ESPN is also taking on the characteristics of social media. It recently licensed its name to Penn Entertainment, a gambling company that can now operate sports books under the ESPN brand. In a previous post, I likened the major social media platforms to gambling, because they’re both addictive and unlikely to provide consistent return for your effort—so you should see your posting efforts as charity rather than labor, and not get too invested in them, in the same way that you’re better off just tossing a relatively few coins into slots at a casino instead of going (literally) all-in trying to change your life there.

Now ESPN will be essentially a vertically integrated gambling operation, offering coverage of sporting events alongside branded sports books and commentary that highlights betting lines, available betting services, and so on. Writing for The Atlantic, Amanda Mull sums up how complete the victory is for the sports gambling complex over the once-gambling averse North American sports leagues and the media that cover them, all of whom need this money to make up for the decline of cable/satellite and the unsuitability of streaming revenue as a replacement:

Although ESPN in particular is still enormously profitable—to the tune of billions of dollars a year—the decline of cable has made continued growth look difficult, and growth is what shareholders want. No matter how creatively you do the math, streaming subscriptions are unlikely to make up the difference. Media executives go where the money is, and right now, the biggest piles of new money are available to those who encourage viewers to gamble. If even ESPN can’t hold out, and apparently has no desire to try, then no one can.

Sports gambling was social media before “the Facebook” was a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye, in that it instilled both FOMO and compulsive behavior, and this integration of ESPN with Penn only exacerbates this characteristic of it by making any consumption of sports content going forward a potentially anxiety-ridden, Web 2.0-esque experience in having to contribute your own part—you can no longer just passively watch, you have to get in on the literal action by betting.

Just as social media can be understood as the replacement of paid newspaper and magazine subscriptions with free ad-supported and engagement-driven websites, the new gambling-centric ESPN can be seen as the replacement of the pay-TV package with tons of gambling cash, both directly from casino operators and indirectly from the individuals who’ll feel the need to gamble.

It’s like social media, in that it makes us feel like we’re workers or even entrepreneurs on the verge of riches, when in reality we’ve become lost in non-remunerative addiction. The only way to win is not to play; you have to have the courage to pull an Elaine Benes in “The Bizarro Jerry” and say:

I can’t spend the rest of my life coming into this stinking apartment [my note: replace with website, channel, app, whatever] every ten minutes to pore over the excruciating minutiae of every single daily event!

-

Nothing makes me feel older than saying that ESPN used to operate a MVNO from a carrier that no longer exists, with Sprint having been absorbed into T-Mobile. ↩︎

-

In 2006, whirl away from home at Yu-Gi-Oh! tournaments, I checked sports scores on my Motorola RAZR with a weird Java app that was costly if I used it for more than a few minutes. ↩︎

-

I put “AI” into quotes because I think it’s a misnomer that assigns too much agency to the rote practice of applied statistics. ↩︎

-

ESPN+ is a streaming service, but it has a much smaller catalogue of high/profile events that ESPN proper. ↩︎

-

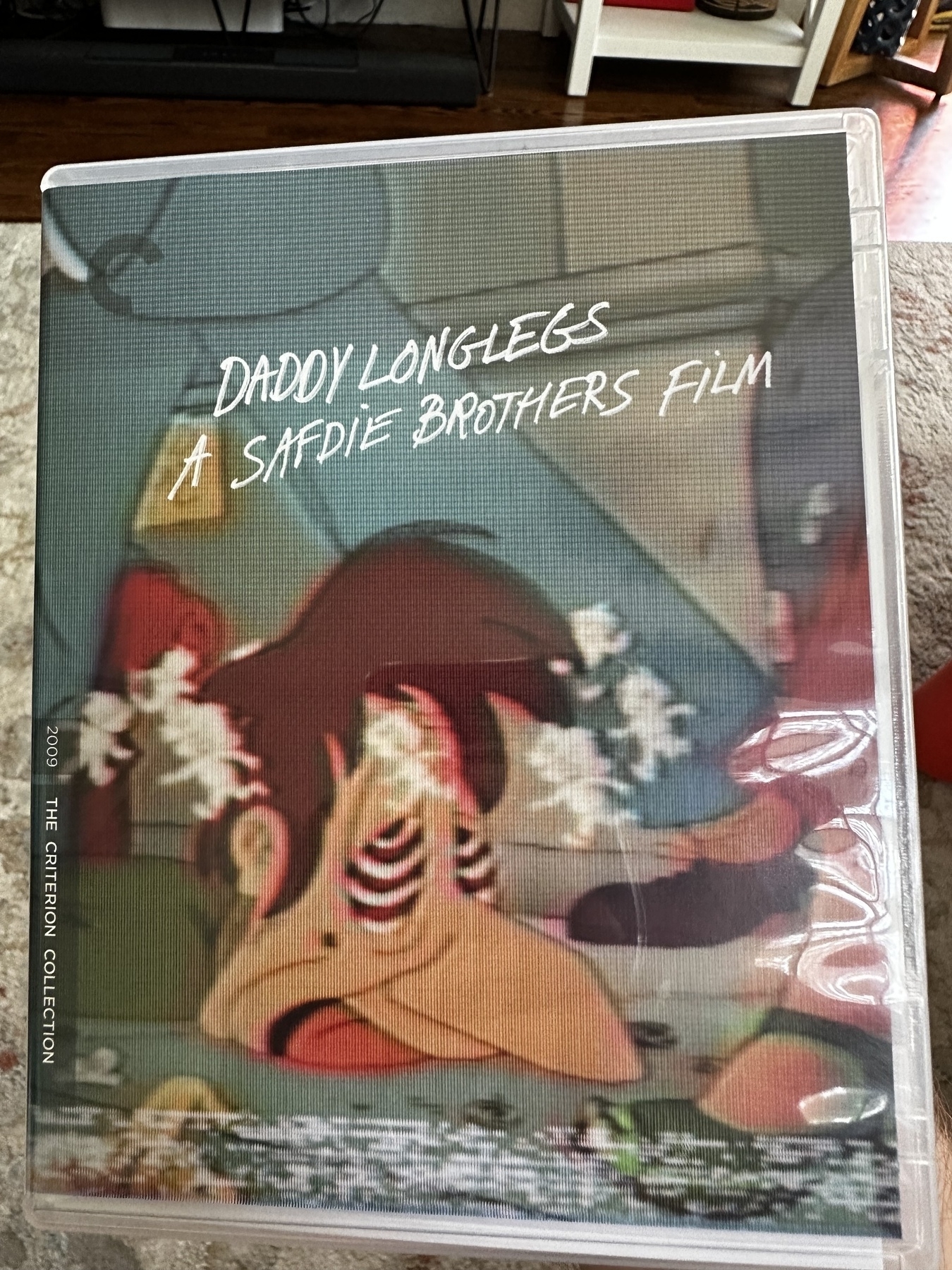

Watched Daddy Longlegs by the Safdie brothers. Tense, terrifying, and yet funny in their distinctive style, even more so than Uncut Gems. The extras on the Blu-ray are fascinating, including a fake CNN spot about Benny Safdie (Edward Teller in Oppenheimer!) boarding a plane to rapturous applause.

-

Today’s morning listens:

- In Stormy Nights by Ghost: This vinyl edition of this psychedelic band’s final album has a different sequencing and one extra track compared to the digital edition.

- Sea of Thee by Maayan Nidam: A characteristically great record from the Perlon label.

-

Batteries not included (or required)

AirPods seem like such a fixture of our world that it’s weird to think they debuted only seven years ago. In that short time, they’ve not only become ubiquitous 1 but have reshaped social norms around:

- Disposability: The batteries in AirPods are small and thus short-lived. Within a few years, they won’t hold a charge—and they’re not user-serviceable.

- Music quality: AirPods use Bluetooth, which is as Steve Jobs himself might’ve said, “a bag of hurt.” It doesn’t support lossless quality—something Apple Music has marketed as a big differentiator vis-à-vis Spotify—and it often introduces noisy wireless interference that’s never plagued wired headphones.

- Social isolation: Whereas wired headphones send a clear signal (pun intended!) to the outer world that you were listening to something or talking to someone, AirPods don’t. They’re hard to see from some angles and overall very small.

Ian Bogost examined the third issue in depth in 2018, talking about how AirPods—by being so inconspicuous—pointed to a world in which we withdraw more and more into our devices, a prediction that now seems dead-on given the upcoming Vision Pro:

[E]arbuds will cease to perform any social signaling whatsoever. Today, having one’s earbuds in while talking suggests that you are on a phone call, for example. Having them in while silent is a sign of inner focus—a request for privacy. That’s why bothering someone with earbuds in is such a social faux-pas: They act as a do-not-disturb sign for the body. But if AirPods or similar devices become widespread, those cues will vanish. Everyone will exist in an ambiguous state between public engagement with a room or space and private retreat into devices or media.

I’ll add that they also amplify anxiety. They make certain critical sounds, such as those from car engines, less audible, meaning possible danger becomes less apparent and multitasking—withdrawing into music while looking out for threats—more stressful. And then there’s the mercurial battery life, which can vary widely between each individual pod.

One time I showed up at the gym thinking I had a full charge in both of them, but one was totally empty despite its indicator, and so I could only listen in mono 2 for an hour of exercise. I was in “private retreat” as Bogost describes it, but only partially because I wasn’t isolated in what I really wanted. So I had neither isolation nor immersion in the moment—just someone talking in (one of) my ears.

Discharged from anxiety

That event plus my overall awareness of how rapidly AirPod battery life declines has made me a wired headphone acolyte anew. It’s like 2004 again when I wore the white earbuds that came with my click wheel iPod.

Seriously, if wired headphones didn’t already exist, you’d sound like either a genius or a madman pitching the idea of a device that:

- Never has to be charged

- Easily handles a lossless signal

- Can fit comfortably in your pocket

They’re almost too good to be true when conceived of in this way. And I’ve embraced this freedom from batteries elsewhere, too.

I got an Apple Extended Keyboard II that’s fully powered by its Apple Desktop Bus connection to my iMac 3, unlike the stock keyboard that comes with the computer. For my Nintendo Switch, I use the HORI Split Pad Compact in handheld mode—it’s more comfortable than the Joy Cons, has a proper D-pad, and never has to be charged.

These battery-free connections reduce one source of anxiety—will my AirPods work, are my controllers ready, do I need to recharge my keyboard—and remind me that there’s no such thing as total isolation. The type of wireless retreat into fantasy that Bogost feared is just that—a fantasy that’s built on the notion that we don’t even need a literal lifeline to something else, that we can really just power on our own with our short-lived batteries.

-

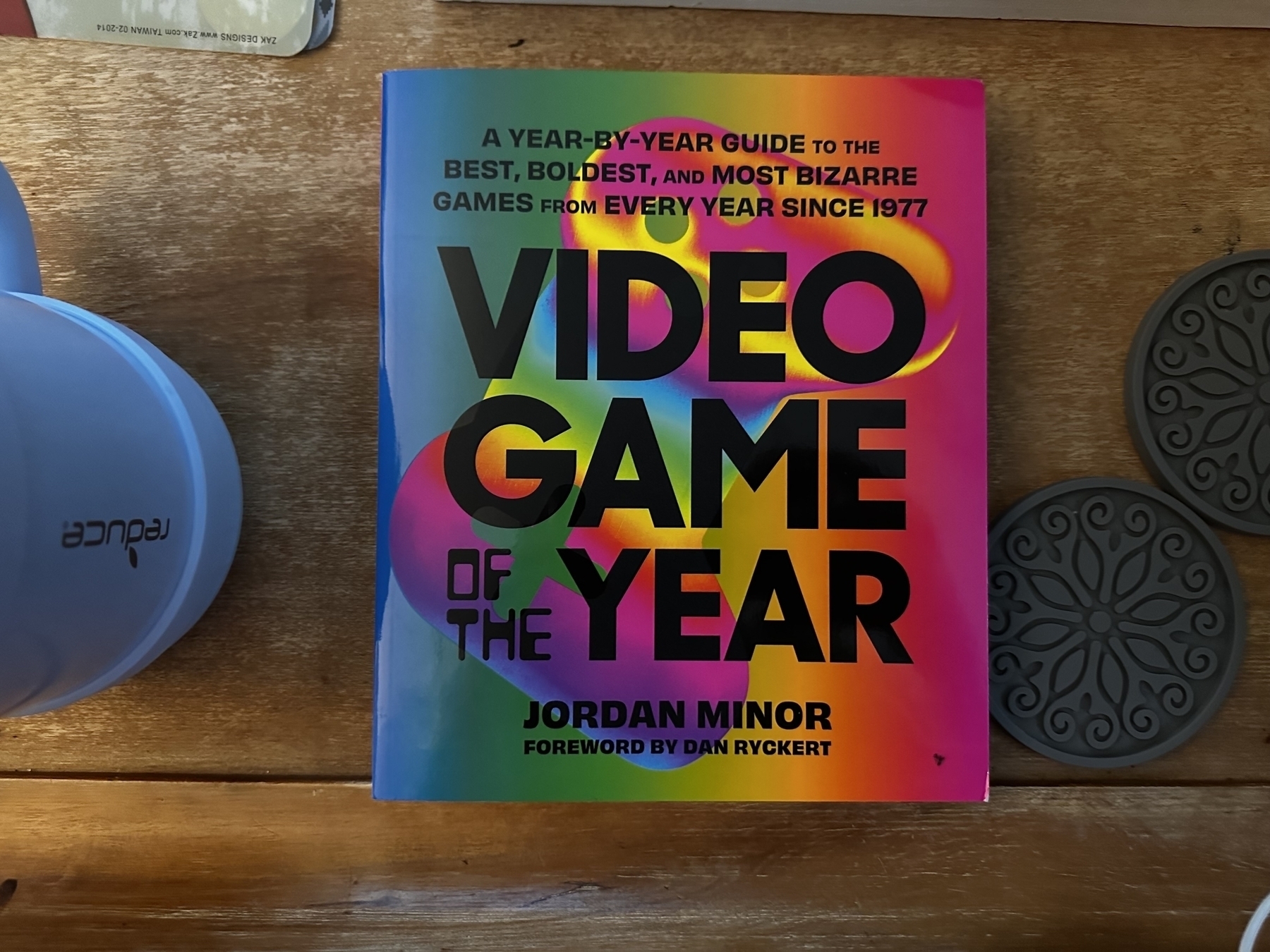

Really excited to dive into this. I like that they had the courage to pick Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest for 1995—the rare sequel that’s better than its predecessor; and imo, the SNES game that holds up better than any other. That music!

-

🌺 blooming

-

Dragonflies

-

Miserable adventures in Threads land

I was among the first few thousand Facebook users 1. Some time in the summer of 2004, my dad 2 emailed me to say that I was eligible to sign up for something called The Facebook as a way of meeting other incoming freshmen at my college. So I became an early adopter of the platform at a time when it was still for .edu domains only.

“The facebook”

That institution had also distributed a physical “facebook” of the class, just as it did physical course catalogs and registration cards. All of these would be retired during my time there, replaced by fiercely proprietary and unfriendly alternatives, but none saw a replacement with the imperial impact of The Facebook.

After signing up via a Dell tower PC, the first person who requested that I “friend” them was an acquaintance—a loose tie, someone I’d been friendly with but not exactly a friend— from a summer camp I’d attended two years earlier in New Jersey. I’d done such camps after each year of high school, and their denouements were always awkward affairs, wherein we swapped email addresses and AIM handles (but rarely if ever phone numbers 3).

It was a ritual with no corresponding reality—I kept in touch with virtually no one, even the people I excitedly exchanged a few emails with before they stopped responding. But now The Facebook promised something far stickier.

Logging into The Facebook in September 2004 let me:

- Do precise search: Type the name of almost anyone I knew from those camps from years ago and I could instantly see everything from what classes they were taking to what music they liked. Moreover, those interests were hyperlinked—you could click say “The White Stripes” and see everyone in your network who also listed them.

- Post on their “walls”: Almost at exactly the time my first classes began, Facebook rolled out the “wall” feature that in its earliest form was like a 1:1 digital equivalent of the dorm room door front whiteboards that everyone at my 2003 summer camp liked to use to relay messages. It was one big canvas that anyone you were friends with could edit.

- Send messages: The Facebook allowed frictionless messaging within the site, like AIM but even better, without the clunky desktop installation. Everything happened in the browser, and it was fast.

I used Facebook 4 almost every day from 2004 to 2014. My peak year was probably 2005, when it combined to be both a class research tool, a dating application, and a way of discovering music and movies. It was the “everything app” before the iPhone made that sort of thing more difficult by encouraging smaller-scale apps.

Until 2006, when the NewsFeed fundamentally changed the experience of using Facebook and the site opened up to non-.edu domains, and 2008, when the App Store launched, Facebook was somehow both super exclusive and boundless in its ambitions. Using it felt like being in on a betting secret—you smiled in the secret knowledge and insight you had, and ironically in the splendid isolation it conferred among your growing network of connections.

Facebook becoming more public from 2006 onward dissipated this aura somewhat, but the inner glow was still so radiant that it was worth staying and posting there. This time all the way through 2016 was what I’d call social media’s “imperial era,” when it seemed like there was nothing it couldn’t replace, that it was immune to any checks on its growth, and that it’d only connect more people with time.

The end of social media’s imperial era

And yet the sun eventually sets on all empires.

My own usage tapered off after 2014 as more of my actual friends left the platform or curtailed their own usage. The platform also became overrun with ads and posts about the 2016 election, the latter a crossed Rubicon not only for Facebook but for all of social media in terms of how even casual people came to perceive it—that is, not as a friendly, fun place to hangout, but as just another flamewar-laden forum akin to the ones it’d replaced.

Indeed, 2016 was the pivotal year that inaugurated our current social era, which is defined by:

- Massive entrenched incumbents floating unsettlingly atop a sea of political turmoil.

- Nonstop “content” consumption that commoditizes both what’s being made and who’s making it to an almost comical degree

- A countercurrent of standardization, led by the W3C, to weave social media into the fabric of the web itself through new protocols such as ActivityPub

No hyperscale or groundbreaking new 5 social network has so far launched after 2016. Both TikTok and Mastodon, which between them embody all three trends above, launched that year and seemingly every new network since has been a variant of one of them:

- TikTok has what Eugene Wei has called a “purity of function as an interest/entertainment graph” aside from any social networking capacity; you can reach millions as a complete rando. Everyone from Instagram to Spotify has attempted to imitate this function by flinging “content” at you with all the immediacy of streaming, but with none of the tedium of having to consume anything in a 30-to-60-minute chunk, all while moving beyond the constraints of the unidirectional following/follower model of Twitter (i.e., you can follow someone without their permission) or the even more restrictive bidirectional one of Facebook (i.e., your “friend” has to agree to your connection request).

- Mastodon was designed as an anti-Twitter: A completely FLOSS 6 implementation of a microblogging service that anyone could install on a server and use to connect to anyone else running the same software. No ads, no post-serving algorithms, no massive centralized server farm—Mastodon almost feels like the early Facebook, before it had any obvious future as a commercial behemoth.

While these two networks were creating new paradigms for what social media would become, Facebook and its far smaller but still-influential counterpart Twitter were coming under unprecedented scrutiny.

The 2016 US presidential election marred both of them permanently:

- Facebook became associated with Cambridge Analytica and with fake ads saying Michael Jordan had endorsed Donald Trump.

- Twitter became infamous as the latter’s preferred communications channel.

Their boomerization and commercialization were complete and with them those transformations, they both became like different types of bars you’d not want to visit regularly. Facebook felt like the site of constant brawls blurred into incoherence and non-reality by alcohol, while Twitter became like a rundown speakeasy, with forbidden and valuable knowledge attainable only by courting risk, not least from the abusive people within it.

Yet these two have proven very difficult to dislodge, because social media after 2016 is not friendly to newcomers, for the following reasons:

- Regulatory scrutiny: Tighter regulations, especially in the E.U., have made the classic social media model of hovering up as much user data as possible to run ads against untenable. Meta, Facebook’s parent, has struggled in the E.U.

- High interest rates: Startups can’t access the capital to build out the infrastructure and footprints necessary to compete with the incumbents on scale.

- Moderation burdens: The chaos of 2016 made the toughest part of social media—moderation, which is in a sense the product of any social media provider, because it determines what you see—even tougher as platforms had to decide how to handle contentious content.

- Network effects: Facebook (2004) and Twitter (2006) had virtually no competitors when they launched. But today’s new social platforms have to dislodge people from the older sites where they’ve cultivated hundreds of even thousands of connections over the years.

Making a social network after 2016 is sort of like trying to make a desktop-first app after 2008. That was the year that both Dropbox and Spotify launched, with Windows and macOS clients as their main interfaces. Most mass-market apps of their ilk would today never target the desktop first, due to the proliferation of phones since then and the rise of web apps, but some smaller developers still focus on it. 7 In both cases, the people still trying to make it work are playing for a niche audience.

The zombie Threads

Even the hyperscale operators themselves aren’t immune.

Meta launched Threads, its purported “Twitter killer,” on July 5 and the app quickly became one of the biggest sensations in the history of the App Store and Google Play, racking up over 100 million accounts in just a week. For comparison, there are only 14 million total Mastodon accounts, accumulated over 7 years, as of this writing.

On paper, Threads has all the ingredients to vault over the hurdles detailed above:

- It’s built on an existing social graph (Instagram) and as such people come to the platform with a built-in audience.

- It’s backed by Meta’s extensive data center infrastructure.

- It didn’t launch at all in the E.U., thereby avoiding regulatory scrutiny there. Writing off those hundreds of millions of users is something only a company like Meta that has so many other profits centers could afford.

- It’s designed to de-prioritize politics and hard news, letting it preemptively avoid the heat that cooked Facebook and Twitter for a lot of people.

Meanwhile, the parade of other Twitter rivals can’t compare on these particular metrics:

- Mastodon, my favorite of the bunch, isn’t meant to be a commercial colossus and is truly a “start from nothing” experience for a lot of people because it’s both technically daunting and has no system for importing or recommending accounts to follow. Infrastructure and speed vary widely from instance to instance.

- Bluesky is still invite-only, which likely killed any chance it had of soaking up fleeing Twitter users en masse. It’s also a Mastodon ripoff, nominally committed to “federation” that still hasn’t happened and that won’t use the ActivityPub protocol if it does, either. It couldn’t even handle a surge in traffic on July 1, when Twitter briefly DDoS’d itself.

- Substack Notes made it so that you signed up for the newsletter of anyone you followed, meaning you’d have inbox overload pretty quickly. It also has horrible moderation.

- Post.news, Spoutible, and other attempts to make a centralized, commercialized Twitter clone are the most prone of all these options to encountering the post-2016 barriers to traction.

But is Threads good? Reader, it’s not even engaging. It already feels like a dead site, with a confusing UI, algorithmic feed, and heavy censorship. If any platform was going to dislodge Twitter as the favorite tool of the media and influencer classes for text based interactions 8, it was going to be this one, but even it couldn’t make it work!

Moreover, because it’s essentially just another way of interacting with the Instagram graph, Threads feels impossible to break through on for anyone who’s not already famous. There’s none of the DIY almost-meritocratic 9 ethic of Mastodon, where someone who posts funny and useful things can quickly rack up hundreds of followers. No, Threads is not really for you or I (unless you’re, like, Netflix incarnate); it’s for advertisers who wanted out of Twitter.

In her newsletter 10, Mariya Delano described the debut of Threads as “a brand-new social media platform is launched with those old hierarchies firmly rooted in place…The people who already had status on Twitter or Instagram are getting to keep that status.” It’s new, but it feels zombielike, like someone pulled some pre-2016 code out of an old file and refactored it. Low-stakes non-political posts, memes, celebrity “main characters,” highly visible follower counts—it’s all back.

Whereas in recent years the likes of Mastodon as well as the very platform where I’m posting this blog—Micro.blog—have de-emphasized metrics, algorithms, and anything that could turn social media into any kind of competition, that’s all Threads consists of. On Mastodon, I have more followers that many people who tried migrating over from their multi-thousand follower count Twitter accounts, simply because I’ve put in more time than they on the ol' pachyderm platform. Their Twitter clout was worth nothing on Mastodon. But on Threads? I’m no one, while people who barely post at all have infinite followers, because their fame elsewhere ports easily to the platform.

Delano sums it up as a setup that instills an immediate feeling of being an outcast:

When I opened Threads for the first time, my brain reverted to that of a panicked and insecure teenager. Meta’s new social media app made me feel like I was a loser nerd, walking into a new school’s cafeteria. And as always, the popular kids could smell that I didn’t belong.

It’s the same feeling I felt as my own social graph began moving on from Facebook and new ones moved in, seemingly with many more reach right away.

Threads is a zombie, and like a zombie it’ll be hard to get rid of. Meta will keep trying to make it fetch. In his groundbreaking novel Zone One, Colson Whitehead talks about the unusual sight of seeing a zombie out in the wild in a world in which everyone is committed 24/7 to controlling their presence, and this sensation is similar to how I feel seeing Threads dominating the social network landscape like 2016 never happened (emphasis mine throughout):

The skel wore a morose and deeply stained pinstripe suit, with a solid crimson tie and dark brown tasseled loafers. A casualty, Mark Spitz thought. It was no longer a skel, but a version of something that predated the anguishes. Now it was one of those laid-off or ruined businessmen who pretend to go to the office for the family’s sake, spending all day on a park bench with missing slats to feed the pigeons bagel bits, his briefcase full of empty potato-chip bags and flyers for massage parlors. The city had long carried its own plague. Its infection had converted this creature into a member of its bygone loser cadre, into another one of the broke and the deluded, the misfitting, the inveterate unlucky. They tottered out of single-room occupancies or peeled themselves off the depleted relative’s pullout couch and stumbled into the sunlight for miserable adventures. He had seen them slowly make their way up the sidewalks in their woe, nurse an over-creamed cup of coffee at the corner greasy spoon in between health department crackdowns. This creature before them was the man on the bus no one sat next to, the haggard mystic screeching verdicts on the crowded subway car, the thing the new arrivals swore they’d never become but of course some of them did. It was a matter of percentages.

And now I’ll leave you by unpacking how the italicized passages relate to Threads:

- something that predated the anguishes: Threads wants to be a social network from before 2016, when TikTok didn’t exist, Donald Trump was still a fringe figure, and social media was more favorably regarded overall.

- his briefcase full of empty potato-chip bags and flyers for massage parlors: Threads has lots of users, but its posts are mostly junk, nothing I want or need to read—“celebrity posts” as Delano notes, plus lots of meta commentary on the state of different platforms, very little news, lots of recycled jokes.

- stumbled into the sunlight for miserable adventures: It’s new-ish, it’s not Twitter, and that can feel liberating. But the experience of using it feels like a step back to the imperial era of social media, and therein lies a lot of algorithmic misery and disillusionment, e.g. feeling bad that other people’s content is very clearly getting noticed more.

- the thing the new arrivals swore they’d never become but of course some of them did: It wasn’t long ago that many people saw Meta’s sites—Facebook especially, but also Instagram and WhatsApp—as artifacts for Boomers and aging Millennials. All the cool kids were on TikTok or any of the many Twitter successors. And yet many of the once too-cool crowd are now right back on a prime Meta property, posting pictures of their lunch like the Boomers they swore they’d never become.

-

Apparently it didn’t reach 1 million officially til December 2004. ↩︎

-

Boomers got Facebook at a very early stage, presaging its dominance with that demographic. ↩︎

-

Long-distance was still a germane concern. ↩︎

-

It bought its current domains, sans the “The,” for $200,000 in 2005. ↩︎

-

A big carve-out, and for a reason. ↩︎

-

Free/libre and open source software. Such software is free to study and modify as you see fit, as long as you follow its license. However, it might not be monetarily “free,” hence the need for the “libre” to distinguish it from “gratis” software. ↩︎

-

I’m writing this blog from MarsEdit on an iMac, so hell yeah I still believe in boutique desktop software. ↩︎

-

The deeper competition is from TikTok, although I think there’s still a chance it gets banned in the US. ↩︎

-

I think meritocracy is a problematic concept, but we can use it loosely/relatively here I guess. ↩︎

-

Make sure to subscribe! ↩︎

-

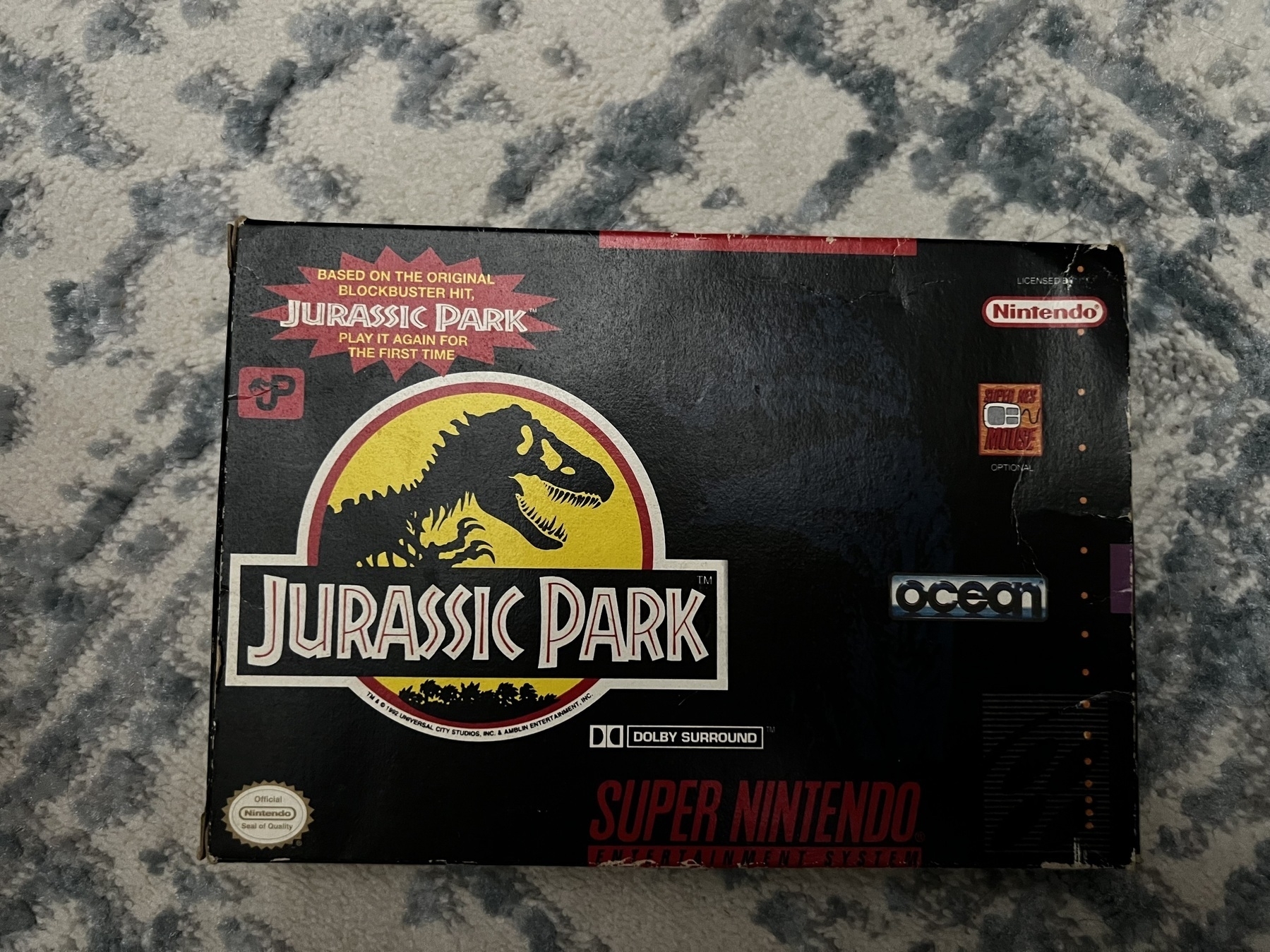

Limited Run Games announced it was reissuing the two SNES/NES/Game Boy Jurassic Park games for modern consoles. Here’s a CIB Jurassic Park for the SNES. Notably it has a Dolby Pro Logic soundtrack and can use the SNES Mouse in controller port 2 for certain sequences like the computer terminals.

-

My grandpa had a grove of Chinese 🌰 trees. They yielded lots of fruit, and were very compact. In contrast, the near-extinct American 🌰 could grow to 100 feet tall and would’ve still been a common site in his youth in the early 20th century.

-

Same location 30 minutes apart in Lombard, IL

-

🦋 🐝 photos from around the garden

-

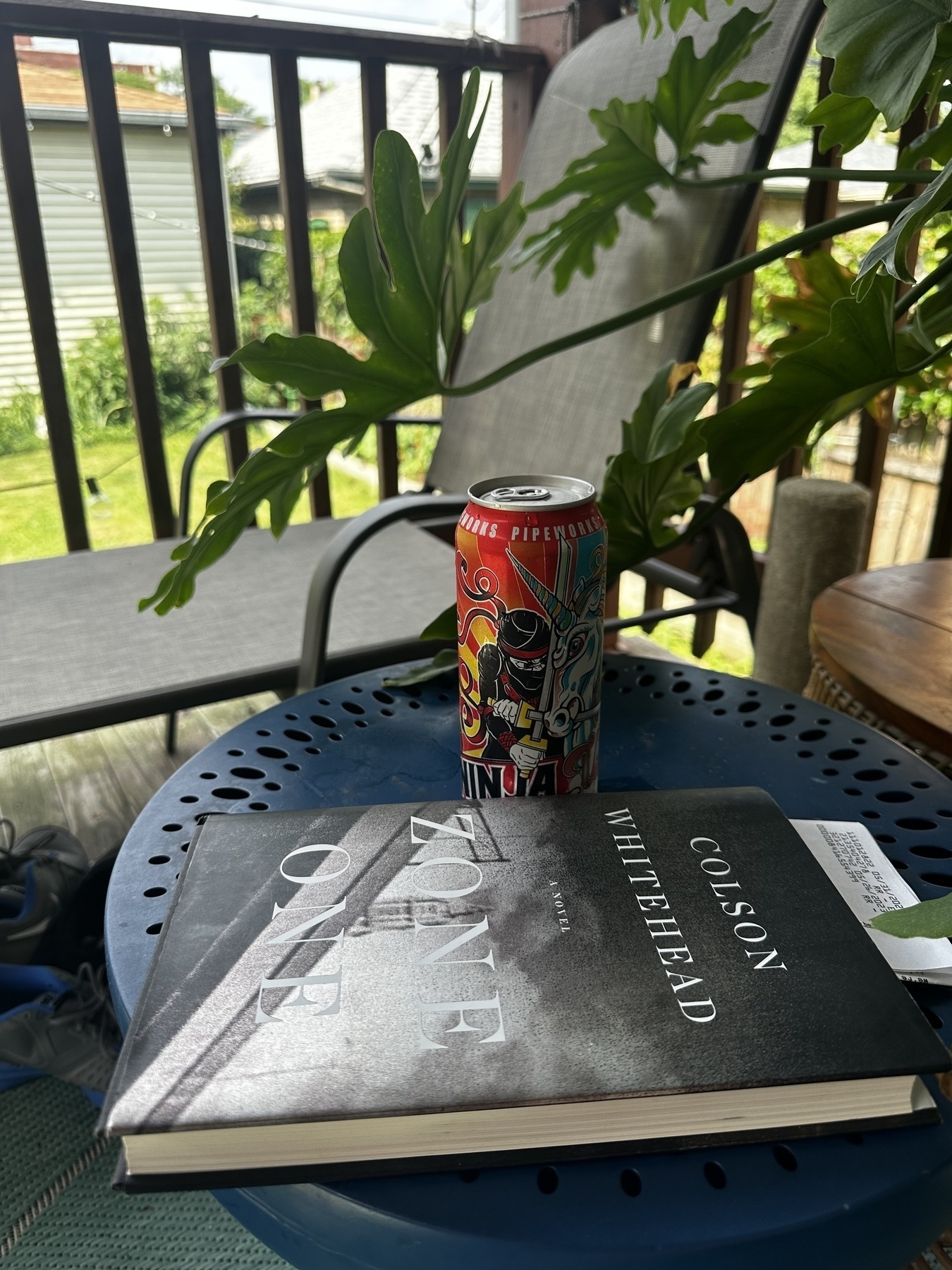

Some light reading while almost sweating to death the other day

-

Snagged this picture of a monarch butterfly on the milkweed before it flew over to the neighbor’s garden

-

Some very KJV-like language from Colson Whitehead in Zone One:

They would force a resemblance upon it, these new citizens come to fire up the metropolis.

Their new lights pricking the blackness here and there in increments until it was the old skyline again, ingenious and defiant.