-

Little squirrel keeping watch

-

iPod Syndrome and the FOMO machine

Staring at a blank page in Microsoft Word1 can be a traumatic experience. Not only is it empty, but the huge range of features, add-ins, and settings within it can also make you feel like there’s just too many potential ways to fill that void, and how will you ever pick the right one? “Here’s every imaginable option—good luck!”

iPod Syndrome

This crushing feeling isn’t unique to Word.

The first time I deeply felt it was with the iPod circa 2004, after I’d ripped every one of the hundreds of CDs I owned onto a Dell tower PC via iTunes. That app showed you the duration of your entire library; mine was ~28 days after finishing the ripping. I’m positive there were songs I ripped on my very first day of iPod ownership that I never listened to all the way until I retired my last iPod Classic in 20122.

Excess was built into the iPod from its conception, indeed, it was memorably marketed as “1,000 songs in your pocket.” Here’s Steve Jobs upon its 2001 launch (emphasis mine):

With iPod, Apple has invented a whole new category of digital music player that lets you put your entire music collection in your pocket and listen to it wherever you go.

On one of my previous blogs, I perceived such excess negatively, dubbing it “iPod Syndrome” and defining it as “one of the most noticeable effects of being deluged by ‘content’…the way your head can feel foggy and your body exhausted by needing to scroll through endless menus and apparently infinite choice.” A college friend had summed up the result of this “syndrome” as:

The more music you have, the less of it you listen to.

Long ago, Microsoft would’ve been my go-to avatar for what induced this feeling, due to the obvious complexity of every part of Office. Word’s bloat scared me off from even diving into writing at times. But now, it’s Apple—because beneath the simple exteriors of the company’s devices are the most efficient machines ever built for accessing content and inducing decision paralysis:

- Apple Music boasts 100 million songs and 30,000 playlists, all ad-free.

- The App Store generated over $1 trillion in sales and billings in 2022.

- Infinite-scroll social media is better built-out on iOS than any platform, thanks to clients that Android and desktop OSes can’t match3.

All of these interfaces, available 24/7 via my phone that’s always with me, induce a lot of anxiety for me. There’s more than could be consumed in a lifetime, and I’m left feeling like I did in 2004—that I have everything with me, but that I can’t sort through it all. I end up wishing for fewer choices, more constraints, anything that could force a decision for me.

One of my last clear memories of music before the iPod was bringing a Discman with me to a coffee shop in Rhode Island, with just one disc in it and no others with me. I got to explore the album I had with me through repeated listening instead of jumping between options looking for the next fix.

The FOMO machine

Constraints like that one make it so that FOMO (fear of missing out, which is foundational to iPod Syndrome) is less of a burden, because there’s no illusion that you have access to everything at all times. FOMO bites hardest when you have:

- No structure, either to your time or what you’re doing.

- Too many options, such that more than one of them seems “right.”

- Deep insight into what other people are doing, so you can see that they’ve chosen something different (and surely better than whatever you did).

Recently on Mastodon, someone described would-be Twitter rival Bluesky as a FOMO phenomenon, driven by people anxious for invite codes (you can’t just sign up). But once they’re there, they don’t seem to post that much, and they end up back on Twitter (or Mastodon, the platform that Bluesky diehards look down on).

That’s how FOMO works: It sacrifices the moment for something that’s never as good as you imagine. It appeals only because you don’t have it and because it seems to present an infinite canvas, which once you find it, isn’t infinite at all because you don’t have the capacity to ever “finish” exploring it.

Bluesky isn’t some unspoiled social media utopia, some Arcadia in the clouds; it’s smaller than most big subreddits, and pretty boring. Likewise, all the music among the practically infinite options out there, which I figured had to sound better than whatever I wanted to listen to at any point in time on my iPod or on any music device/service since then, was often not as satisfying—I was listening to my Anjunabeats records because I liked them, not because I was using them as some stopgap til I found the real prize.

So I try to keep my media libraries small and not spend too much time wondering if I’ve made the optimal choice. Life’s short and I don’t want to lose a lot of it in scrolling and debating what to listen to, what to watch, what to read. Going with the first thing that comes to mind is often much more satisfying than a drawn-out decision.

-

I don’t write in Word anymore, but it’s inescapable both in many work environments and the publishing world. ↩︎

-

I finally retired it after Google rolled out its Play Music locker (I was an Android user at the time) in the early 2010s. In typical Google fashion, that service no longer exists. ↩︎

-

Granted, the recent changes to the Twitter and Reddit APIs means that many iOS-only clients for their services have vanished, but the platform still has a clear lead in apps for all the Fediverse services, such as Mastodon. ↩︎

-

Saw this little one while watering the plants in the backyard

-

Apple Vision Pro reuses the Vision branding of its 90s CRT displays. A Q&A page for one is still up:

Macintosh computers only have one sound-in port. The AudioVision sound-in port, however, gives you an easy way of swapping between two inputs. For example, you may want to digitize music from a CD player, but when the phone rings you want to use AudioVision as a hands-free speakerphone.

-

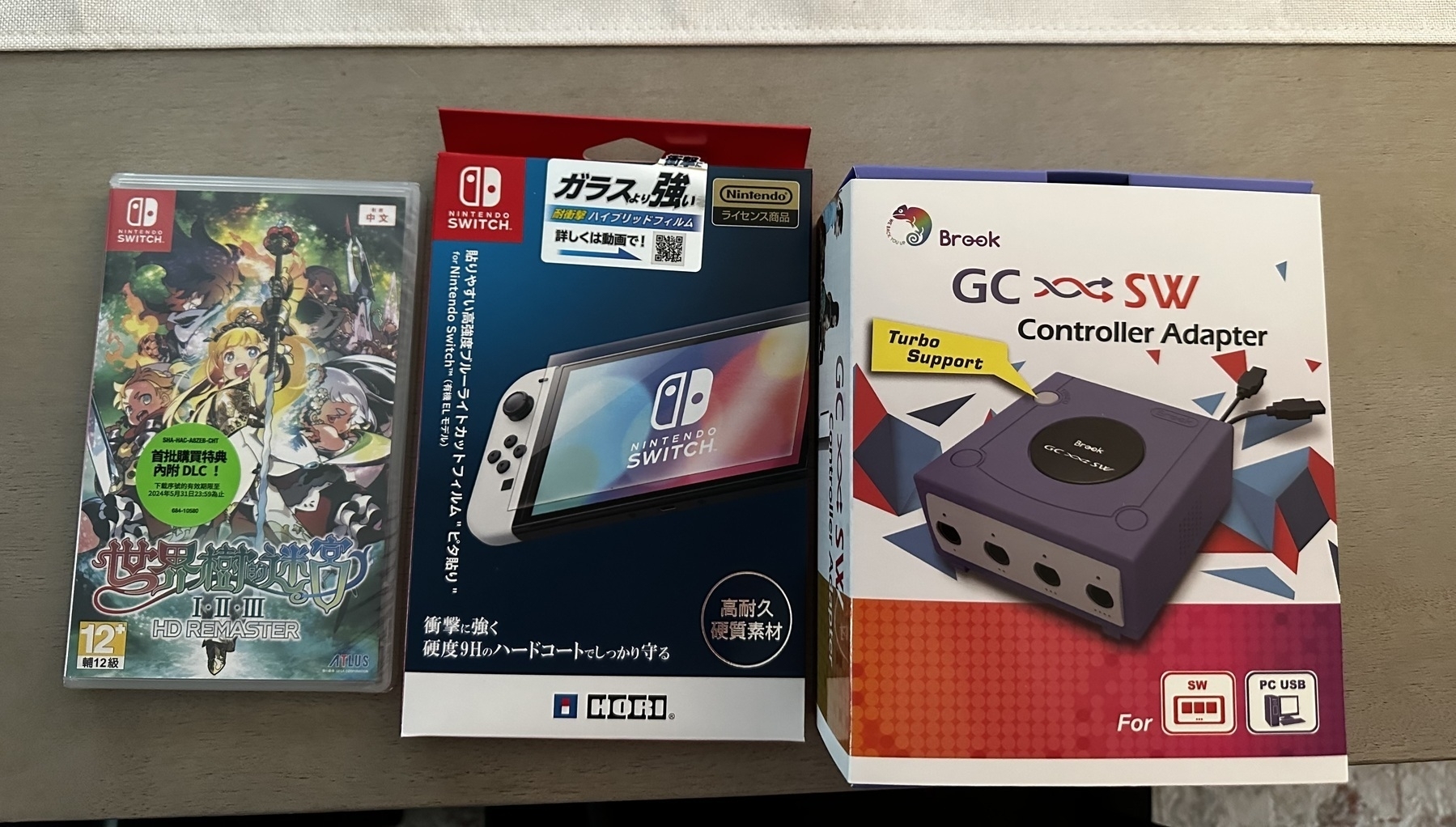

Latest Play-Asia haul:

- Etrian Odyssey Origins Collection

- Switch blue light screen protector

- GameCube controller adapter

-

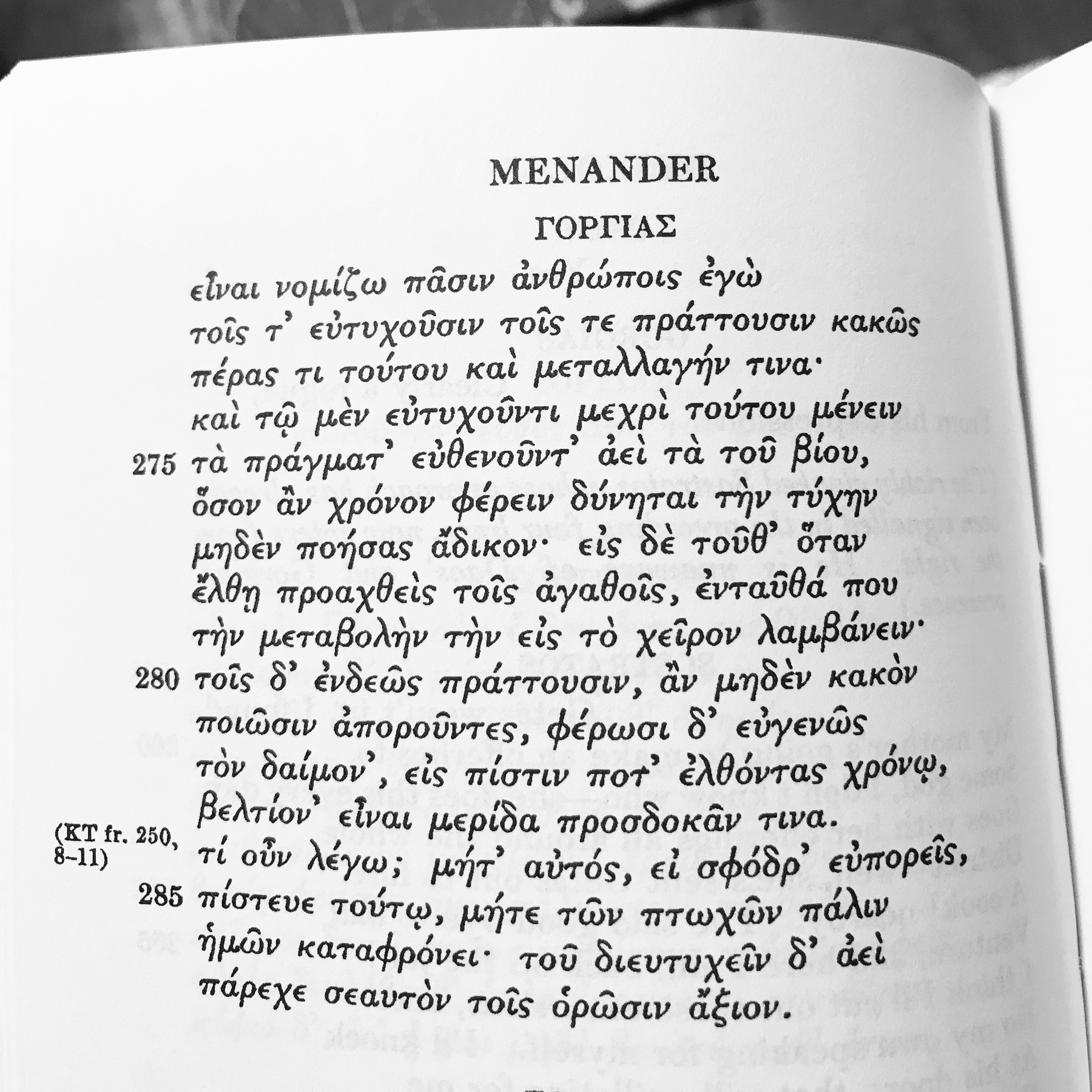

Part of The Grouch by Menander. The speech is about how both the affluent and the destitute can see their fortunes reversed. My translation of the first line (alt text has full page):

Among all men—the successes as well as the failures—I think there is a flip-side to their positions in life.

-

Afternoon relaxation

-

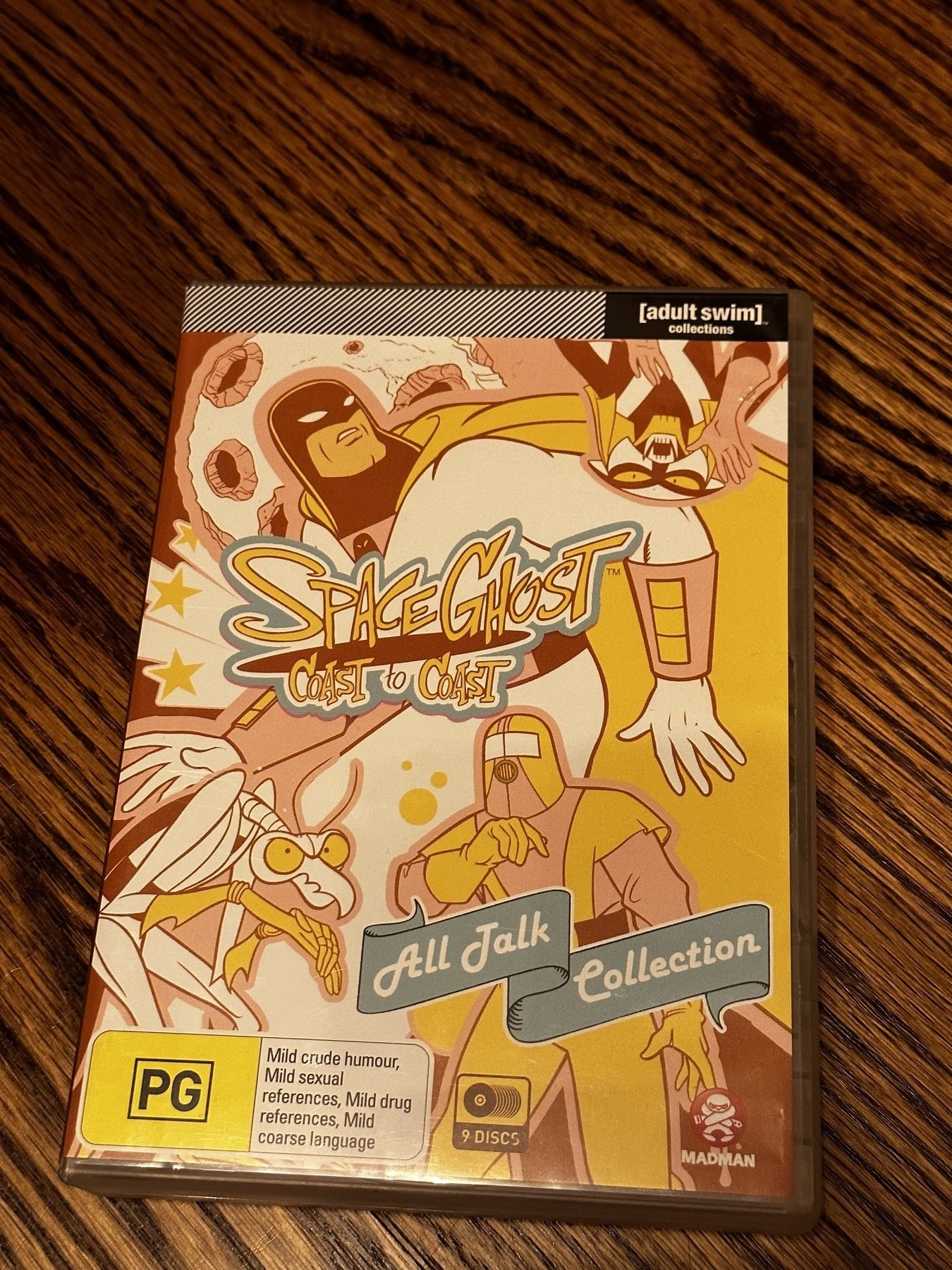

I bought this complete DVD box of Space Ghost Coast to Coast in 2013, and am glad to have it now that the show has vanished from Max. It includes the rare vols 4 and 5, but is a Region 4 exclusive. I play it on a region-free 2008 Philips DVD player with thick component cables for a throwback feel.

-

Test post

EDIT: Appears to work just fine. I updated a bunch of pages in my blog’s custom theme to get my favicons to work and wanted to ensure I hadn’t broken anything. This page was helpful in outlining how to set up site.webmanifest and browserconfig.xml as static text files within templates.

-

Robin perched on the fence, looking at another robin out of frame. They’re regulars in our backyard.

-

The only way to win is not to play

In 1999, I rented Final Fantasy III1 for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Immediately overwhelmed by its complexity, I went scrounging2 for tips online and found a full-length guide someone had uploaded to a then-new site called GameFAQs3.

I printed (!) it out, took the little pile of papers upstairs to my game room, and referred to it frequently throughout my 33-hour playthrough. As of this writing, that guide is amazingly still up, with the seemingly immortal detail “Updated: 03/17/1995.”

The road to content creation

Untold amounts of online “content” have in the interim gone through their entire lifecycles of creation, adulation, monetization, resentment at their lack of expected clout-building, and finally destruction, across numerous platforms, some now-extinct and other lumbering on with their users clinging to their digital dinosaur limbs:

- MySpace was conceived, rose to dominance through autoplaying music and easily editable HTML, was bought by News Corporation, lost all value and most of its users, had all its pages purged, and tried a weak 2.0 relaunch.

- Facebook was borne out of Facesmash, went from Thefacebook dot com to sans-the, hawked Wirehog, introduced the NewsFeed, pivoted to video, and ultimately became uncool.

- Blogging went from a niche and technically daunting task to something trivially easy to get started with, having passed through the guts of Blogger, Livejournal, Typepad, Wordpress, and Substack.

Meanwhile, that humble FF3 text file, a relic of the Web 1.0 era when internet users were mostly sharing nice stuff with no brands to build or ads to run, has sat unchanged by its maker for 28 years, yet still helping untold ranks of gamers navigate a wonderfully complicated game—for nothing, monetary or otherwise salutary, in return. Almost as if its charitable, rather than commercial, purpose has let it outlast reams of clout-boosting content.

Granted, FF3 hasn’t been updated, either; it predated the era of DLC4 and live-service games. But this FAQ has never gotten so much as an SEO refresh, gone behind a paywall, or been used as a springboard for building—for its writer—a glitzy online reputation through a major social media following that’d then rake in millions in presumably inevitable ad revenue.

Its free, immediate availability indeed feels like an act of charity—and I mean that as a good thing, even though a lot of Extremely Online people today would take the opposite stance and say that such a giveaway is bad, that the author did unpaid labor for GameFAQs, that they should’ve been looped-in on the site’s ad monetization somehow, and that giving away free stuff is bad for brand reputation.

In other words: No freakin’ way we could comfortably deem the FAQ’s author a real Content Creator.

Content creation is gambling, not work

As a leftist, such arguments about not “working for free” are intuitively appealing. Labor deserves compensation. But is posting a type of labor? Is it a job? No, it isn’t.

I think we’re confusing the distinctive addictiveness of platforms such as Twitter and YouTube, when used in a personal capacity, with work.

They hook you with the prospect of lots of re-shares of your content and perhaps fame (!) and even maybe fortune (!!) from there, but inevitably they let you down, at which point—if you don’t just quit or resign yourself to the fact that social media posting is not a road to riches or even to subsistence wages—you feel compelled to either go even harder (see the entire right-wing-coded “rise n’ grind” economy) or to resign yourself to a more satisfyingly left-ish “I’m being exploited and I should be paid by the platform itself!” stance.

Either way, you see yourself working even though you’re (almost certainly) actually just bummin’ around, unless you’re a professional content marketer. And both mindsets center the nebulous concept of “content,” which implies something that’s:

- Hosted in someone else’s container: You’re on a stranger’s platform, whether that’s Twitter, YouTube, or somewhere else5, but contra most people’s understanding, that place is more like a casino than a workplace.

- Meant to be monetized: Related to the above, what you create is at its root designed to enrich “the house,” in this case, the platform owner, and this is obvious from the start or with a bit of cursory research. “Content creation” is risky like gambling, with lots of effort channeled toward dubious chances of remuneration.

- Constantly in need of more work: Once you start creating content on someone else’s farm6, you enter a doom loop of needing to work on greater amounts of it without seeing greater rewards for it—like a gambler needing to place continually bigger bets to sit out of a hole. Exhaustion and frustration (and maybe ruination) ensue. But as a Content Creator, you feel like you can’t give up, that fame is still close at hand with a few tweaks, that you’re in the correct fight.

On Substack, Brian Feldman has summarized the latter feeling well:

The pursuit of likes, followers, attention, fame, and money is framed as inherently good, or a noble struggle. To criticize one’s attempt to earn a living on social media is implied to be punching down and unspeakably rude. This discussion is often couched in vaguely populist, technical, and legalistic terms. A platform user’s “unpaid labor” and “intellectual property” is being “monetized” and “exploited” by the forces of “late capitalism,” and users are at the whims of “the algorithm” which “lacks transparency” — but if the participants in the platform’s “economy” were to band together, they could exert pressure through “collective action” in order to access the “profits” held in “creator funds” that are rightfully theirs. This is, when you think about it for like half a second, a myopic and stupid way to think about interacting with or informing other human beings, and yet it is the dominant mode.

Yes.

We’re internalizing the logic of “content” outside of its natural home in the marketing agency world, seeing every attempt at sharing a link, writing a blog, or posting a video on our own time as fundamentally a transaction—and along the way, indulging the quintessentially American fantasy that we’re all just temporarily embarrassed millionaires. We’re telling self-styled Content Creators that they’re right to gamble away their precious time and money, despite the overwhelming evidence that most of us can’t even come close to making social media activity into a real career—and the fact that treating another pull of the online notoriety slot machine as a noble act is just weird.

I get the impulse—the idea that with more posting, the right kind of posting, the 10 Tips for Better YouTube Discoverability, it’ll all work out and you’ll score a victory for labor over capital, and all without having to make content marketing your day job! But the source of your addiction isn’t your actual job, of course—if it were, it wouldn’t be so addictive!

Twitter (or any other megaplatform) isn’t your job

There are certainly people who’ve made social media content creation their life. But to see how rare this is, consider the following platforms and their macro trajectories, and how all of them point to the nature of these places as sites of charity, not labor:

- Twitter: It’s common to say that Twitter’s users are creating “free content” for it, implying that it should be paying them, not the other way around. But no one, not even Twitter itself, has ever made much money from Twitter. Despite the number of site visits, the company at its peak generated about as much annual revenue as Olive Garden. Even huge accounts are often forthrightly desperate for money and support, revealing that social media fame has no direct path to money. It’s a bad, sleepy casino, or, if you prefer, a bar—a place to hang out with no expectation of becoming galactically rich and famous, but to instead dispense jokes, threads, and links as charity.

- Bluesky: Twitter’s would-be successor is small but its early adopters—who’ve gotten invites via their own prominence or adjacency to someone else’s—are eager to “scale” it, and with that scale…do what, exactly? Bluesky is so clearly just a place to shitpost without worrying about Elon Musk twiddling with his dials. It has no concrete plans for either better moderation or monetization, let alone some way for Content Creators to mine its veins. It’s just a place to have fun! Or it would be, if engagement weren’t through the floor, despite its users snootily acting like Mastodon is the network with those problems.

- Mastodon: Mastodon has no illusions of being a place of potentially remunerative labor. There’s no ads, no way to algorithmically boost your content, no revenue sharing. These features are some of the big reasons I think clout-chasing Bluesky users dislike it—there’s no clout to be bought, no audience to upsell, so the gambling of time and money on grind-like content creation immediately reveals itself as foolish. Better to just relax and share some cool links about the old AppleVision monitors.

- Reddit: Reddit users, as Feldman points out in their article, seem to recognize that what they do is charity. They post helpful tips and links that wouldn’t make it through the Google SEO ringer without adding a special “Reddit” operator to the query. They’re not workers destined for slices of revenue, and they know it. Their rebellion against Reddit’s recent API changes shows more than anything that the charitable (free) sharing of Reddit’s posts across the open web, rather than the transactionalism that Reddit leadership envisions, is what they value most.

Social media may fulfill a basic need for community, but trying to win at it, rather than enjoy it and share knowledge freely without the expectation of every bit going into a spreadsheet invoice, is going to always be disappointing. The only way to win is not to play—and to instead find actual games and other activities that you like. The best parts of the internet—Wikipedia, the Fediverse, and the Internet Archive—are essentially volunteer-run charities that survive on donations. That’s the model for enjoying your time online.

-

Know as _Final Fantasy VI _in Japan. The second, third, and fifth installments of the ironically never ending franchise had not been localized in North America at this time. ↩︎

-

Google existed but IIRC I hadn’t found out about it yet. So I probably used Dogpile? ↩︎

-

GameFAQs’ design has roots in Usenet, where “frequently asked questions” pages were common as repositories of knowledge in the days before easy web search. ↩︎

-

Downloadable content. Not long after FF6, Nintendo did experiment with some early DLC with its Satellaview add-on for the SNES, though. ↩︎

-

It’s funny how the big, centralized platforms have taken us back to the days when the internet was considered a discrete location rather than a continuous medium. ↩︎

-

A “content farm” is an organization that churns out content at industrial scale in an attempt to capture Google traffic. I highly recommend this rundown of how they work. ↩︎

-

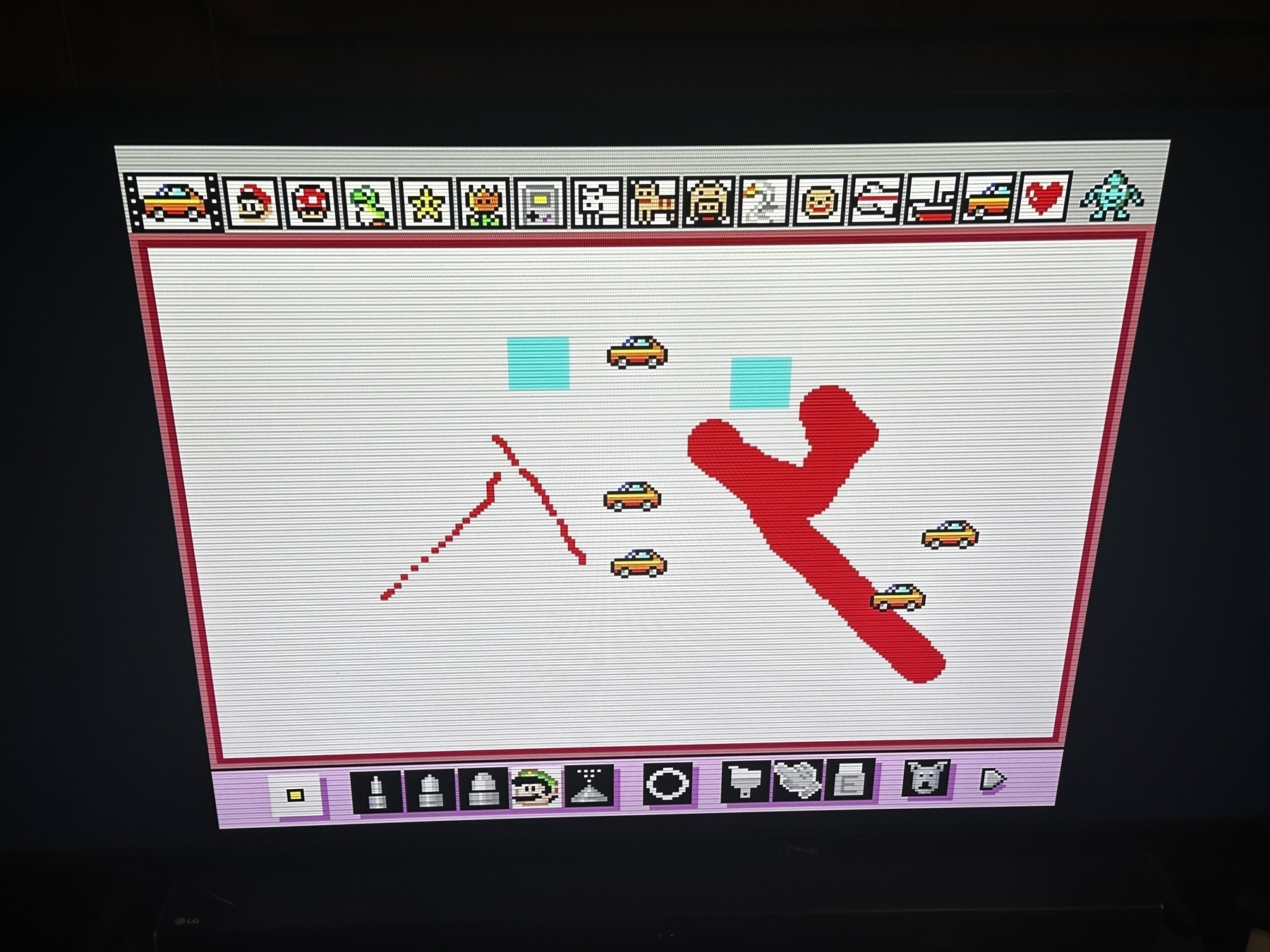

My nephew’s trying to learn Mario Paint, seen here running off of the original cart in 1080p, 8:7 aspect ratio via an Analogue Super NT. Using a Hyperkin optical mouse instead of the official Nintendo ball mouse.

-

Colson Whitehead imagining the post apocalyptic device landscape in Zone One:

His parents were holdouts in the age of digital multiplicity, raking the soil in lonesome areas of resistance: a coffee machine that didn’t tell time, dictionaries made out of paper, a camera that only took pictures.

-

Micro Monday! Brandon’s Mid-Life Reset by @BrandonWrites, a nice blend of topical content and posts about games and music. I enjoyed the recent Friday The 13th The Game post, which gets at the important issue of impermanence and delisting in the age of digital distribution.

-

Why print encyclopedias still matter:

a little voice in the back of my head reasoned that it would be nice to have a good summary of human knowledge in print, vetted by professionals and fixed in a form where it can’t be tampered with after the fact—whether by humans, AI, or mere link rot.

-

Faded gnome (used to have a red cap) keeping watch over the garden

-

Ensuring text accessibility is a key part of my day job, and it’s influenced my personal life, too. I set my blog theme to black text on a white background because that’s the most legible combo. I’ve also gone back to the Light theme on macOS.1

-

I still prefer Dark on iOS due to OLED display ↩︎

-

-

Plants and books basking in Saturday sunlight from open windows

-

The first game I ever had on CD was King’s Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow. Its copy protection was a book of symbols you needed for a riddle. I remember how hard it was to find that info online back then, because I either lost the book or couldn’t find the guide on the disc.